SALAMA CUENCA

INTRODUCTION

This is the first report concerning ARI-ARIMA archaeological investigations in Guatemala. It is offered as a brief history of the development of Arqueologia Regional Integrada de Mesoamerica (ARIMA) and to document ARI’s progress in Mesoamerican research.

Archaeological Research Institute (ARI) and Research Applications in Mormon Archeology & History (RAMAH) have been involved since 1981 in independent reconnaissance investigations in Guatemala and Mexico. Since 2005 ARI has been providing an educational grant in Guatemala for a student to gain a degree in archaeology from San Carlos University which will enable recognition by the Ministry of Culture and Deports of Guatemala, the Institute of Anthropology and History (IDAEH), and the Technical Board of Archaeology (CTA).

In 2007 Arqueologia Integrada Regional de Mesoamerica (ARIMA) was formed and recognized by the government of Guatemala as a non-profit organization established as a division of ARI and received approval for excavation and research in Guatemala.

In 2008 archaeologists Kathy Black, M.A.; Joseph Andersen; Glenna Nielsen-Grimm, Ph.D.; Deanne Gurr Matheny,Ph.D. and Ray T. Matheny, Ph.D. joined ARIMA and an excavation proposal was presented to IDAEH. ARIMA also procured the services of archaeologists Juan Luis Velasquez, Sandara Carrillo, Juddy Carrillo, and Bertila Bailey, all Guatemalan professional archaeologists and Grace Vlam, Ph.D., art historian, to assist with the excavation and the permit process.

SITE MAPPING

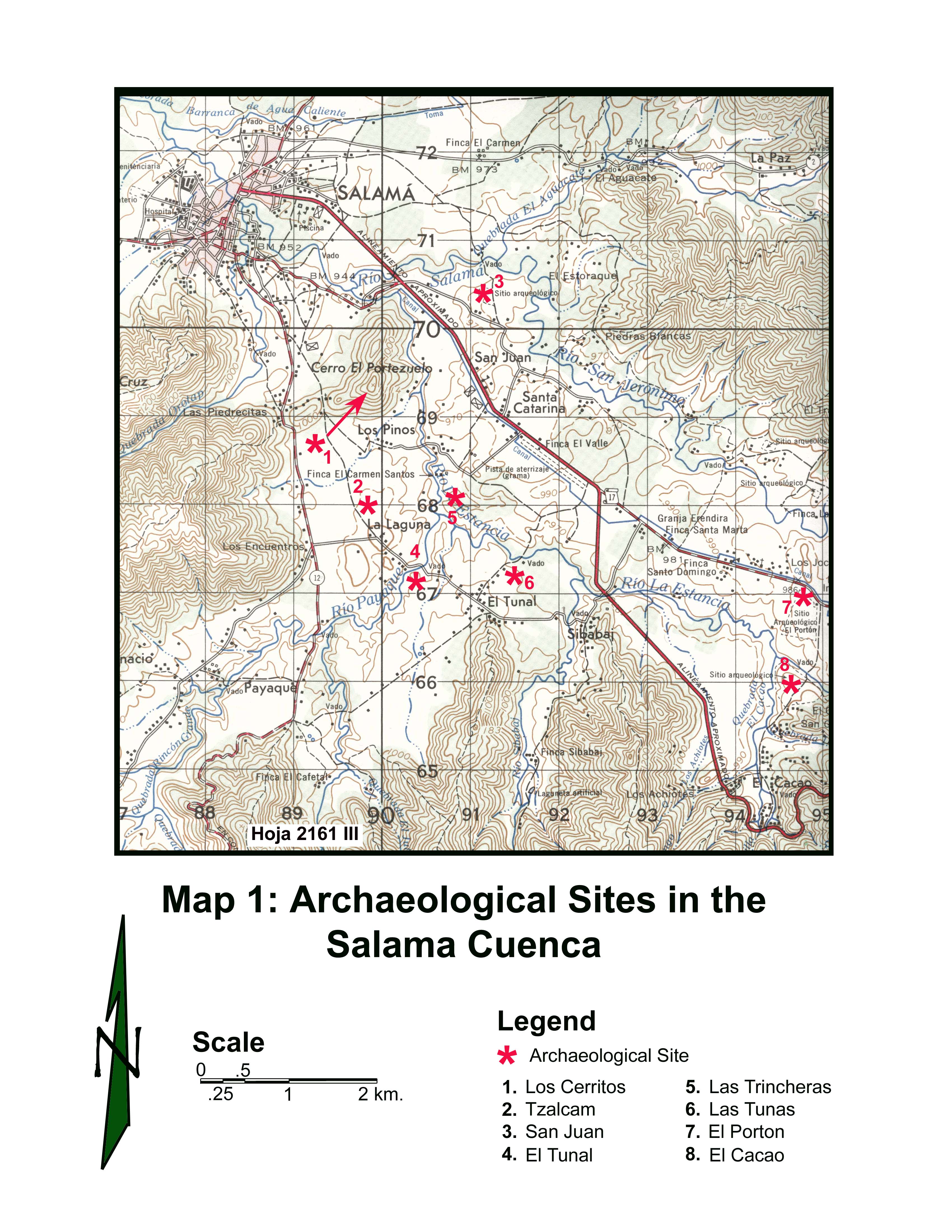

ARI-ARIMA conducted GPS mapping operations on three Preclassic sites in the Salama Cuenca:

Los Cerritos is a hilltop fortification overlooking the Salama and San Jeronimo valleys. It is situated on Cerro de Portezuelo directly north and above the site of Tzalcam. The city of Salama is north of the hill. This site was initially documented as Los Pinos by John Fox in his 1978 publication Quiche Conquest: Centralism and Regionalism in Highland Guatemalan State Development. Sedat and Sharer visited this site in 1972. Their assessment of the site was that it probably dated to the Postclassic period because of its use as a fortification. No diagnostic ceramics were obtained to verify that assessment. These authors’ final comment was: “While probably Late Postclassic and contemporaneous with Pachalum to the east, it could well have supported earlier occupations as well.…the affiliation of Los Pinos (Los Cerritos) with the ethnic Quiche is by no means established” (Sharer & Sedat 1987:246).

The trail to the top of the cerro begins at the base of the hill’s slope on the roadway north of Tzalcam. During the ascent three separate coursed stone wall features are encountered. These walls vary in height and width from less than a meter to over 1.5 meters. The platform on top of the hill has been flattened, its circular periphery defined by a low coursed stone wall. An artificial mound occupies the center of the circular platform. Although apparently intact at the time of the Sedat and Sharer expedition (these authors make no mention of the looted vault), the eastern half of the top of this mound has been vandalized exposing a burial crypt that was stabilized with large stone columns, some of which have been modified with linear engravings that appear to extend around the columns. One of the columns exhibits a perforation that is similar to the cupulate depressions observable on similar stela elsewhere in the Salama valley. The remaining columns are in various stages of collapse and several have apparently been pulled out of the vault and abandoned on the mound’s surface. This looted stone burial crypt was oriented in a north-south direction similar in construction and orientation to Los Mangales Burial 6 and El Molino Burial 1 as documented by Sharer and Sedat (1987:128-150, 220-223). These similarities suggest the Los Cerritos burial crypt may be of Preclassic or possibly Classic origin. Low, circular, coursed rock altars mark the four cardinal directions surrounding the mound’s base.

The ARI-ARIMA mapping operations were confined to the platform and mound complex associated with the hilltop fortification. A GPS instrument was used to map the platform, altars, burial mound and exposed crypt (file 191108A). Future ARI-ARIMA activities at Los Cerritos will include clearing brush, mapping, and test excavations to determine if the site dates earlier than the Postclassic period.

El Tunal is situated on Hoja 2161III (Salama, Guatemala) at 790400mEast and 1667200mNorth, Zona 15, UTM (see Map 1). It apparently consists of a Preclassic residential complex situated on the remnant Pleistocene terrace overlooking the Rio Payaque depression, which is below and to the northwest of the site. The large Preclassic site of Tzalcam is situated on the opposite or northwest bank of that river at an identical elevation.

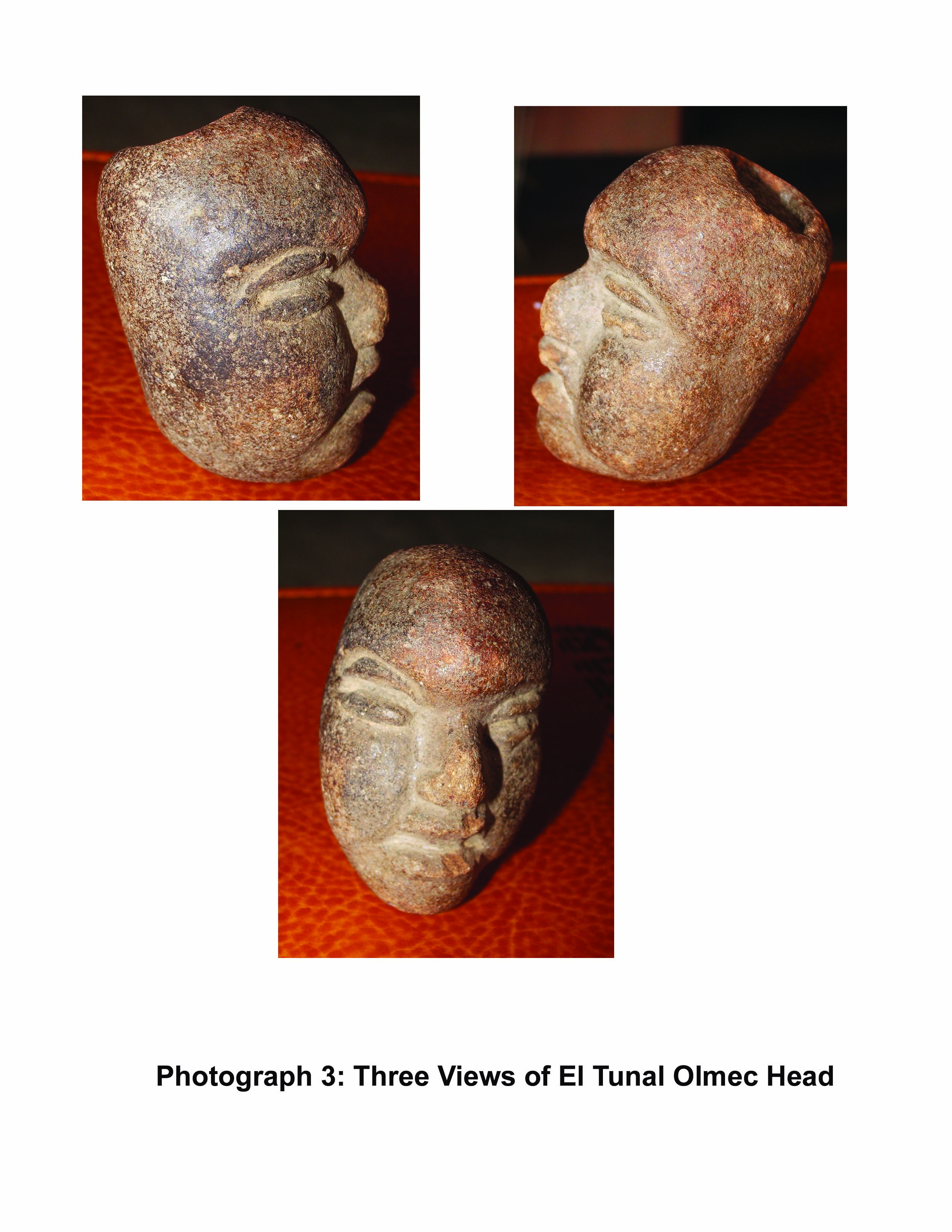

El Tunal was discovered by the land owner while excavating a small pit on the top of the terrace above her home. Although the landowner did not retain any pottery during the excavation, an Olmec ceramic head (see Photograph 3), an animal figurine head, a variety of beads, a partial lithic spear point and several ground stone implements were recovered and retained for curiosity.

ARI-ARIMA mapping operations included the easterly draining slope, the ridge-top to the southeast of the primary ridge (file 211108B) and the slope below that ridge down to the owner’s home. A small pottery collection was taken from recent exposures on this ridge.

Future excavation activities will include cleaning the walls of the existing pit in order to identify any stratigraphic sequences that exist on that portion of the site. Based on the results of that exercise, test pits will be excavated on the tops of the two ridges in order to identify the residential compound that apparently exists on this site.

Las Tunas is situated on Hoja 2161III (Salama, Guatemala) at 791500mEast and 1667200mNorth, Zona 15, UTM (see Map1). It overlooks the Rio La Estancia to the north and consists of a hilltop ceremonial center containing five separate mound and platform complexes that date from the Early and Middle Preclassic.

Excavations at this site were conducted in 1973 during the Sharer and Sedat expeditions (1987:159-187). The Early Preclassic Xox Ceramic Complex (ca. 1200-800 B.C.) was identified at this site but as “redeposited matrices appearing in later construction” (Sharer & Sedat 1987:162). In other words, all evidences of the complex were recovered as diagnostic sherds.

ARI-ARIMA mapped the central and southern portions of the site’s platforms and the two large east-west mounds. The remainder of the platform will be mapped in January 2009. Ceramics were collected and documented from various exposed surfaces of Las Tunas including several partial vessels that were recovered from the dry irrigation pit.

For fieldwork in 2009, ARI-ARIMA recommends that a 2x2 meter test pit be placed in the center of the large platform in order to determine whether a residential complex exists in that location that can be associated with the Early Preclassic Xox ceramic complex. Sharer and Sedat’s work on this site did not include testing the center of the site which would have been the most elevated portion of the hilltop prior to the construction phases linked to the later Max (ca. 800-500 B.C.) and Tol (ca. 500-200 B.C.) Ceramic Complexes. Their assessment of the site was that the original Xox occupation soils had all been extracted for use in building the peripheral platforms resulting in a depression within the center of the site (1987:179). A test pit in the center of the site can confirm whether this hypothesis is correct and will yield Preclassic materials from the aguada depression. However, should their hypothesis be incorrect, the identification of a buried and intact Xox phase occupation would be most satisfying.

RECONNAISSANCE

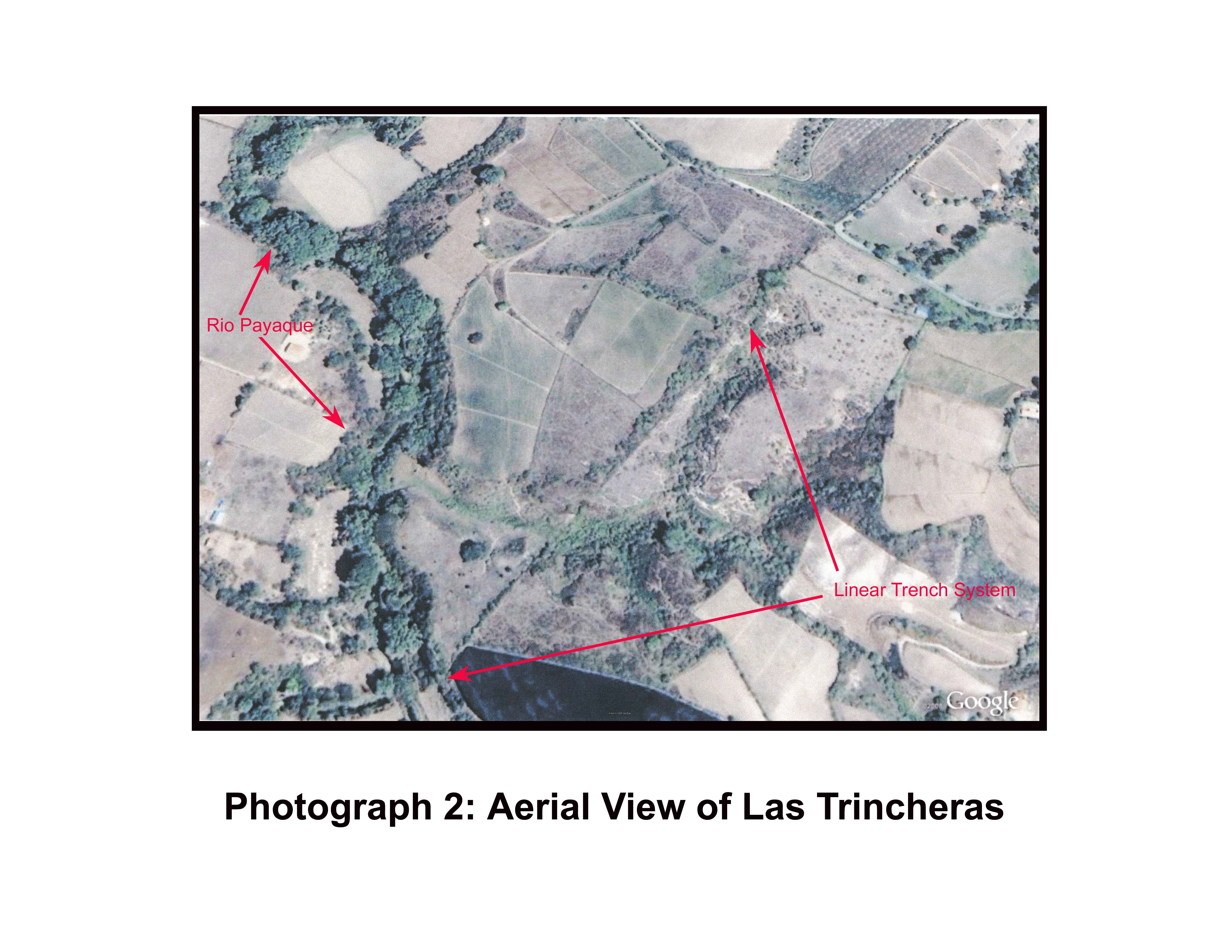

While visiting Las Tunas on November 20, a potential archaeological site exhibiting a variety of what appeared to be low mounds was observed to the northwest on the northern bank Rio La Estancia. During further exploration the author identified a parallel trench system that appears to be of ancient date. That system is similar to other fortified trench systems observed in the Coban region to the north.

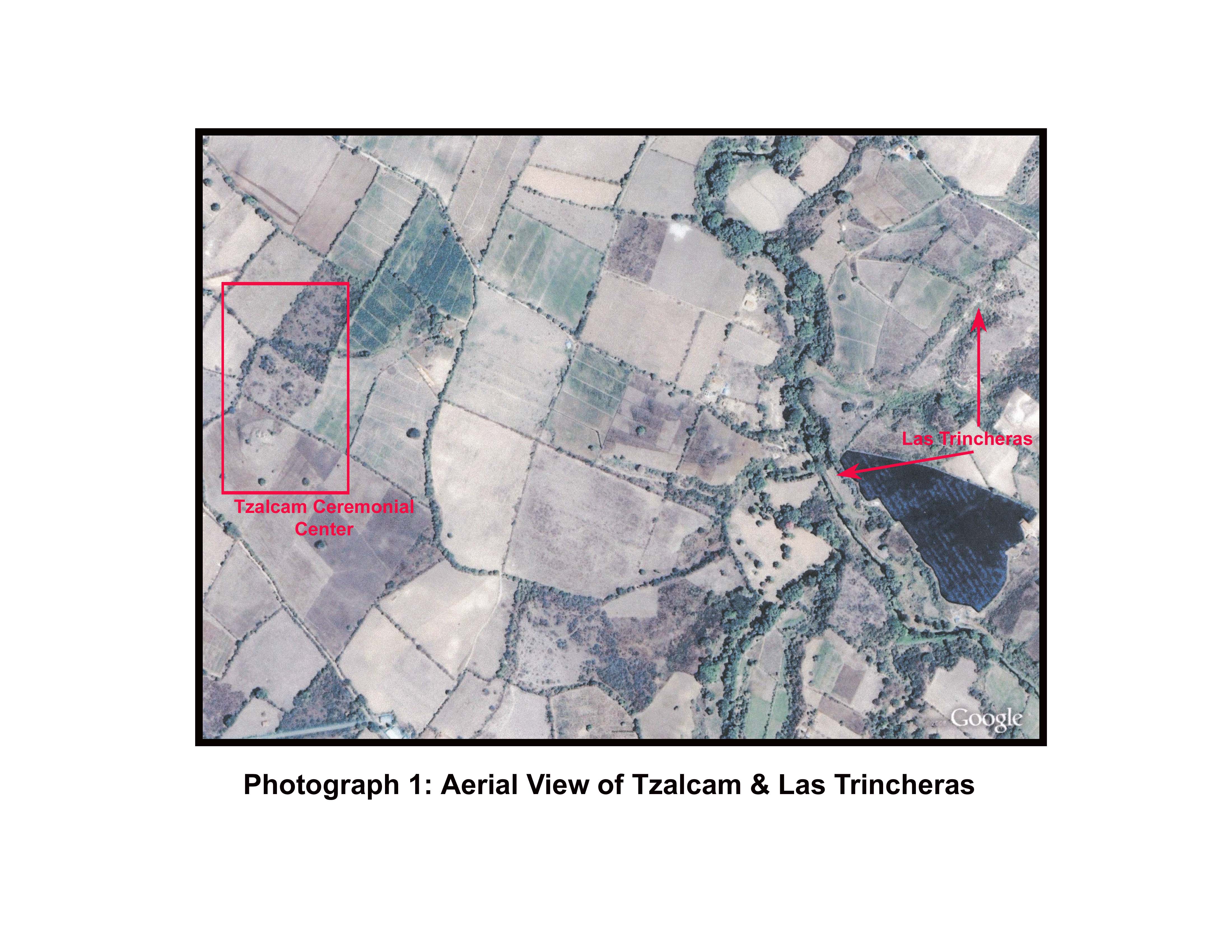

This site consists of two deep trench remnants extending along the edge of the mesa running parallel to the crest of the immediately adjacent quebrada and was subsequently named Las Trincheras 1.

As Photographs 1 and 2 demonstrate, Las Trincheras 1 is situated above the east bank of Rio La Estancia and begins as a single trench at the river bank just northeast of the confluence of the Rios Payaque and La Estancia. From that location it extends in a northeasterly direction up the slope onto the top of the first ridge and in a direct heading crosses the top of the ridge to the crest overlooking the quebrada’s exit channel. There, at the crest two parallel trenches become apparent both descending the slope of the quebrada into its base where they have been apparently filled by alluvium during the course of time. Maintaining the same northeasterly heading the trenches ascend the south-facing slope of the quebrada to the top of the mesa where they parallel the edge of the northern branch of this quebrada for at least 150 meters. At one segment of the trench system the edge of the quebrada has eroded away and that section of trenches has been lost. A deep pocket of trees and brush identify the degraded area. On the opposite side of the eroded quebrada wall the double trenches are again apparent continuing onward for another 30 to 40 meters before disappearing into a thicket of dense brush and trees. Where the trenches go from that location is presently unknown.

ARI-ARIMA will continue the investigation of trenches at Tzalcam and Las Trincheras using aerial photography to facilitate that reconnaissance.

DISCUSSION

The use of trenches for fortifying defensive systems is mentioned by Sharer and Sedat in their investigations at nearby Tzalcam. They state:

“Tzalcam obviously maintained a potentially defensive position with its fairly pronounced gradients, accentuated with terracing on the west, north, and east sides. Only the southeast corner… needed major protective modification. Indeed a ditch and rock wall (not recorded in 1972, but noted by Ricketson along the southeastern corner) might be a remnant of ancient defensive construction in this location….

Potentially defensive earth and stone embankments and a possible ancient ditch suggest that Tzalcam could have been a fortified site” (1987:238).

It is interesting to note that a major east-west cultural discrepancy apparently existed in the Salama – San Jeronimo valley: To the west the Tzalcam community evidently invested extensive energy and community involvement in the construction of walls and defensive trenches, or “ditches.” Based on the new 2008 discovery of the site Las Trincheras, these fortifications actually extended eastward from Tzalcam well beyond the Rio Payaque, which forms a natural defensive line. Fortifications in the forms of walls and escarpments were also recorded by Sharer and Sedat on the sites of San Juan and Las Tunas, both of which are within 2.5 kilometers of the larger Tzalcam (see Map 1).

To the east, in the San Jeronimo portion of the valley, just the opposite seems apparent. There is no evidence of defensive systems at El Porton, the site mentioned by Sharer and Sedat as the dominant ceremonial and organizational center for the region (1987:431-433). Nor are there apparently any defensive systems at the adjacent complexes of El Cacao, Santa Catarina, and Santo Domingo.

Obviously, the rulers and populations associated with El Porton in the eastern portion of the valley had no fear of being attacked by the westerners, but the rulers and population associated with Tzalcam in the western portion of the valley seem to have had every reason to fear being attacked by the easterners.

The questions naturally arise: why did the Preclassic communities in the eastern end of the valley associated with El Porton have no fear of attack? And why did the western communities apparently associated with the large site of Tzalcam have so much fear that they invested an incredible amount of effort in constructing defenses? In addition, were the fortifications at Los Cerritos developed during the Preclassic as a fundamental part of the valley’s western defensive system?

Conflict between communities is invariably linked to two fundamental factors:

1. economic competition for scarce resources, and/or

2. ethnic diversity between populations

If the defenses were the result of economic competition for one or more scarce resources, ARI-ARIMA needs to determine the nature of those scarce resources in the western end of the valley which caused the competition between these two disparate communities. What was it that the western valley people had that they so fiercely protected and yet was so desired by the eastern communities?

Perhaps some type of ethnic diversity existed between these two localities. If so, ARI-ARIMA needs to determine through its excavations what those cultural differences may have been to fuel such intense rivalry. It is apparent in reading Sharer and Sedat that the Maya peoples occupying the eastern end of the Salama – San Jeronimo valley were involved in various forms of ritual that included the offering of sacrificial victims. This type of behavior was not identified during the excavations at San Juan or Las Tunas. It will be most interesting to determine through excavation whether Tzalcam, which was apparently El Porton’s counterpart in the western portion of the valley, will provide similar evidence of ritual behavior or if the buried remnants on this site demonstrate that an entirely different ethnic group was in control of the locality’s resources.

F. Richard Hauck, Ph.D.