Cutting Down a Tree: a Metaphor for Death in Scripture and Mesoamerica

Cutting Down a Tree: a Metaphor for Death

in Scripture and Mesoamerica

by Diane E. Wirth

Copyright © 2015

Throughout the Bible and other ancient Near Eastern texts, trees and parts of trees, such as branches and roots, are sometimes a metaphor for individuals or groups of people. In a genealogical/lineage sense, mankind may be referred to as being planted (Exodus 15:17), while descendants are shoots, boughs, and branches. The righteous are considered green, well-watered, and fruitful; whereas the wicked are bitter, withered, unripe, dried up, nonproductive, and ready to be burned.(1)

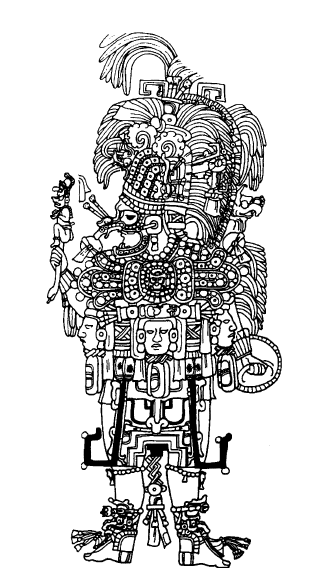

Fig. 1 King as World Tree, Stela F, Quirigua, Guatemala

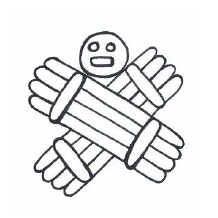

In Mesoamerica, people, especially royalty, were associated with trees, branches and sprouts. For the Maya, kings are oftentimes depicted on stelae as the World Tree personified, ultimately delegated them as the axis mundi of the cosmos (see Fig. 1, Stela F, Quirigua, Guatemala). Their aprons, in these scenarios, have two appendages, one on either side of the apron denoting branches of the tree. In light of this, kings sometimes were called Ajaw Te, “Tree Lord,” considered a royal title.(2) In addition, ch’ok, meaning “sprout” in Mayan Chol, was used to indicate a young member of the royal family (see Fig. 2).(3) By the same token, the lineage founder of a dynasty was oftentimes referred to as ch’ok-te-na, “Sprout Tree-House Lord.”(4) In other words, members of a lineage were considered the sprouts of the ancestral World Tree, which tree the king may represent.

Fig. 2 Maya glyph for child “sprout”, ch’ok

To the west of the Maya culture, the Mixtec of Mexico visualized their royal progenitors being born from trees (see Fig. 3). The Seldon Codex shows a young royal child with umbilical cord still attached to the center of tree. Two serpents are wrapped around the tree. The one on the left has a cloud motif, while the one on the right has what is referred to as “star eyes,” both denoting the heavens where the child originated.(5)

Fig. 3 Men born from trees, Selden Codex

In the ancient Near East scholars have long been aware of the combined imagery of tree and man as contained in Isaiah 11:1, where the forthcoming Messiah is spoken of as a “branch”: “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots.” In this particular scripture, the Hebrew word for branch is semah, meaning “sprout.”(6) As already noted, calling offspring “sprouts” was a tradition among the Mesoamerican culture.

There was a Jewish practice of planting trees when children were born ─ as long as the tree was healthy, the child would remain robust. A cedar was often planted for males and a pine for females.(7) In his commentary on the Dead Sea Scriptures, Theodor Gaster remarked “the life (or soul) of a person is bound up with that of a tree,” and that “Goethe’s father is said to have planted a tree in his garden on the day the poet was born.”(8) Gaster also noted that in the Dead Sea Scrolls (Cp. Gen. 12.10-20), Abram had a dream in which he saw both he and his wife, Sarai, as a cedar and palm respectively, and that these trees symbolized their lives.(9)

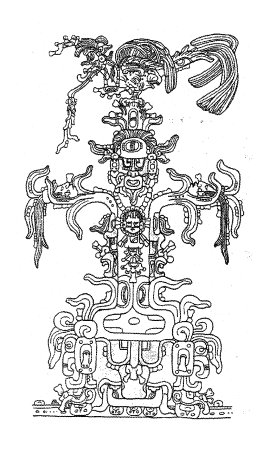

Fig. 4 Maize as World Tree, Codex Borgia

In Mesoamerica we find a similar tradition.(10) First, it must be understood that maize is but one form of the World Tree. Prime examples of maize as the World Tree or Tree of Life are in the Mixtec Codex Borgia with the tree at the center of the primordial sea (Fig. 4), and a relief of the Maya Foliated Cross at Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico, which is also a maize plant/tree (Fig. 5).(11)

Fig. 5 Foliated Cross with Maize as World Tree, Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico

When a child was born, even today among the Maya, a maize seed is planted to represent the child. This association of the newborn united to maize begins with the child’s umbilicus cut over an ear of maize. According to J. Eric S. Thompson, the bloodstained maize is removed from the cob at the appropriate season and sown with great care in the name of the child.(12) This maize is maintained until the individual can plant and harvest his own maize field. This maize plot is associated with him in a very sacred blood relationship. In fact, the maize field is called “child’s blood.”(13) The future of every Maya is intrinsically tied to the life and quality of his maize. Throughout all of Mesoamerica, mankind was thought to have been made of maize by the creator. In fact, Sahagún wrote that cultures west of the Maya who spoke Nahuatl, would express a human being with no hope of living, “a withered ear of maize.”(14)

The Quiché Maya’s story of the Hero Twins in their sacred writing the Popol Vuh, also associates the life of maize with beings.(15) On anticipation of their dangerous trip to the Underworld, which was undertaken in hope of conquering the Lords of Death, the Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xblanque instructed their grandmother to grow corn in the middle of her house. The milpa, that is the maize field, and the middle of the house were both considered the axis mundi, the center of the world.(16) Planted at the center, this maize was therefore associated with the World Tree. The Popol Vuh Hero Twins told their grandmother that if the maize survived, they lived; but if the maize died, it would be an indication of their death.(17) The maize in this story died, but it soon revived due to the miraculous skills of the Hero Wins as they were reborn, having conquered the Lords of Death.

Egyptologist Susan Tower Hollis studied the myths of Osiris, the Egyptian grain god, and his later mythological counterpart, Bata. The fate of these two gods were dependent on the fate of the tree with which they were associated.(18) Tower Hollis remarks, “Whatever happened to the tree ─ happened to the man.”(19) This ideology was certainly true in biblical stories as well as in the Mesoamerican belief system.

An interesting phenomenon takes place in the scriptures with regard to trees or tree parts. They are often cut down or cut off. Looking more closely, we find that people can also be cut down or cut off, just as the tree. The words “cut down,” or cut” and “down” within the same scriptural verse, are used 54 times in the Old Testament, and four times in the New Testament. Those things that are “cut down” are in every instance related to either vegetation, primarily trees, or people. Things that are cut down include: groves, branches, trees, boughs, woods, sticks, flowers, grass, thickets, sprigs, grapes, wooden images, and individual persons or groups. Cutting down images and sacred groves was an act of aggression to destroy what was considered to be associated with idolatry. The cutting down of individuals or groups of people may be done by others, as the wicked are frequently cut down with the Lord’approval. For example, in Ezekiel 31:1-13 the Lord compares Pharaoh to the Assyrian (no doubt a ruler or even the Assyrians collectively), who in turn is compared to a great cedar. So majestic was the tree that all under his boughs envied him. However, his pride equaled his greatness, and consequently the Lord delivered him into the hands of the heathen where they “cut him off, and have left him . . . and in all the valleys his branches are fallen, and his boughs are broken . . . and all the beasts of the field shall be upon his branches.”

Perhaps one of the more famous stories in the New Testament is the allegory of the Olive Tree, especially in Romans 11 where Paul speaks of grafting branches, that is individuals, into the olive tree. Those who are not of the seed of Israel, the Gentiles, but believe in Christ, will be grafted into the olive tree, representing the house of Israel. Those who are born as Israelites, who do not accept Christ, will be “cut off.” Throughout the scriptures, being “cut off” literally means being cut off from God and His influence of the Holy Ghost to attend them. Other expressions similar to being “cut off,” have the same connotation.

We find this type of symbolism in the Book of Mormon. The subjects of King Noah bring Abinadi to him, reiterating the prophet’s words to their king: “. . . he saith that thou shalt be as a stalk, even as a dry stalk of the field, which is run over by the beasts and trodden under foot. And again, he saith thou shall be as the blossoms of a thistle, which, when it is fully ripe, if the wind bloweth, it is driven forth upon the fact of the land.” (Mosiah 12:11-12) These two verses are a clear metaphor of King Noah’s future demise as prophesied by Abinadi.

Gaster noted that the deaths of Domitian and Severus Alexander were both thought “to have been presaged by the falling of a tree.”(20) But even more significant than the “falling” of a tree, is a deliberate cutting down of a tree. Use of the words “cut down” is especially significant in Job. It is here that for man to be cut down like a tree, means death. In Chapter 14 Job testifies of the shortness of life and the certainty of death. “He [man that is born of a woman (Job 14:1)] cometh forth like a flower, and is is cut down: he fleeth also as a shadow, and continueth not.” (Job 14:2)

In a satirical poetic form, Isaiah 14:8 explains the future of Babylon: “Yea, the fir trees rejoice at thee, and the cedars of Lebanon, saying, Since thou are laid down, no feller is come up against us” (see also 2 Nephi 24:8). Continuing, verse 12 speaks of Lucifer being “cut down to the ground,” and in verse 19, “cast out of thy grave like an abominable branch.” These verses refer to the defeat, and even the spiritual death of Lucifer. The analogy of “cutting down” and “spiritual death” can also be found in Helaman 14:18.

Yea, and it [the resurrection of Christ] bringeth to pass the condition of repentance, that whosoever repenteth the same is not hewn down and cast into the fire; but whosoever repenteth not is hewn down and cast into the fire; and there cometh upon them again a spiritual death, yea a second death, for they are cut off again as to things pertaining to righteousness.

The words “cut down” or “cut” and “down” are used in the Book of Mormon with relation to trees or vegetation, and are used in the following verses: 2 Nephi 19:10, 20:34, 24:12; Jacob 5:44. The 2 Nephi scriptures are from Isaiah texts inscribed on the brass plates of Laban and include trees and Lucifer as cited above. Jacob’s allegory of the tame and wild olive trees is of course referring to both trees and individuals or groups of people. Hugh Nibley brought our attention to the similarity of Zenos’ account in Jacob with the Thanksgiving Hymns from Qumran. The watered trees represent the righteous, while the wicked are cut down and burned.(21) To further support the cutting down of a tree may represent spiritual and/or physical death, the metaphor is clear in 3 Nephi 4:28-29.

And their leader, Zemnarihah, was taken and hanged upon a tree, yea, even upon the top thereof until he was dead. And when they hanged him until he was dead they did fell the tree to the earth, and did cry with a loud voice, saying:

May the Lord preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth. [emphasis added]

The tree represented Zemnarihah, and its felling epitomized the demise of this wicked man.(22) In line with this thought, Alma, the prophet of the Nephites, spoke throughout the land, giving a warning to the people: “The Spirit saith, Behold, the ax is laid at the root of the tree; therefore every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit shall be hewn down and cast into the fire . . . . the Holy One hath spoken it.” (Alma 5:52) Again, this scripture is referring to mankind in similitude of a tree ─ the fruit being a symbol of their works.

In most verses “cut off” is not related to trees or tree parts, but this does appear to be the case in Nebuchadnezzar’s dream. In the king’s dream a great tree was seen, and a holy messenger from heaven cried, “Hew down the tree, and cut off his branches, shake off his leaves, and scatter his fruit” (Daniel 4:15, see also verse 23). The tree in the dream was interpreted by Daniel as none other than the king himself ─ another analogy of man and tree, and the “cutting down” of it referred to his future. The wicked are also compared to a cut tree in Job, where Bildad is speaking: “His [the wicked] roots shall be dried up beneath, and above shall his branch be cut off” (Job 18:16), meaning his descendants.

Alma 42:6 makes clear what the phrase “cutting off” means spiritually, that is, being cut off from the Tree of Life: “But behold, it was appointed unto man to die─therefore, as they were cut off from the tree of life they should be cut off from the face of the earth . . . .” Continuing on, verse 9 explains that the “cutting off” results in a spiritual death, or essentially that Adam and Eve were now “cut off from the presence of the Lord,” consequently, the Savior’s mission on earth was essential and necessary to bring men and women back into the presence of their Heavenly Father.

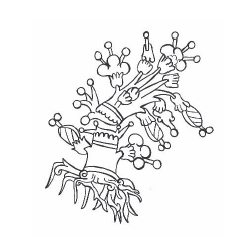

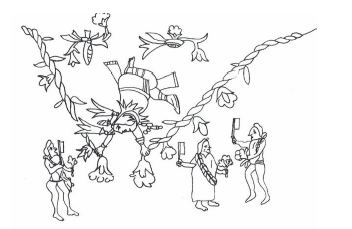

In light of the saga of Adam and Eve being expelled from the Garden of Eden, there is an interesting tradition found in Mesoamerica regarding the first couple in the creation story that took place in Tamoanchan, the garden with a paradisiacal setting especially made for them. Tamoanchan was a place where there existed no death, no pro-creation, and a state of happiness. Xochiquetzal, the first woman, cut a flowering fruit from a special Tree in the garden. In the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, the Tree is seen as cut and bleeding (Figure 6).

Fig. 6 Bleeding and cut Tree in Tamoanchan, Codex Telleriano-Remensis

The result was a wounded and literally broken tree, and the expulsion of Xochiquetzal and her husband from the heavens to the earth (Fig. 7 from Codex Vaticanus). According to Michael Graulich, cutting a flower from this Tree resulted in death for future humans on the earth; while the broken, severed tree represented the end of face-to-face communication with the creator couple in the topmost heaven.(23)

Fig. 7 Xochiquetzal falls to earth after plucking a flower from the Tree in Tamoanchan, Codex Vaticanus

What happened to the tree happened to the man, and this scenario was common in both the ancient Middle Eastern and Mesoamerican thought. The concept goes back to the very roots of the cosmic World Tree, even to the Tree of Life that was from the beginning of creation. Those who led righteous lives were fruitful, as was the Tree. Those who were wicked suffered the demise of cut trees that perished.

Cutting a tree in both the Old World and New Worlds had a most definite meaning to the cultures that lived on these continents separated by the seas. The well-being of the trees and their parts, was a metaphor for the spiritual state of individuals or groups of people.

Notes

1 John A. Tvedtnes, “Borrowings from the Parable of Zenos,” The Allegory of the Olive Tree: The Olive, the Bible, and Jacob 5, Stephen D. Ricks and John W. Welch, eds., (Salt Lake City: Deseret and FARMS, 1994), 387-93.

2 Linda Schele, Workbook for the XVIth Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas (Austin: University of Texas, 1992), 45.

3 Schele, Workbook for the XVIth Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas, 45.

4 Schele, Workbook for the XVIth Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas, 156.

5 Jill Leslie Furst, “The Tree Birth Tradition in the Mixteca, Mexico,” Journal of Latin American Lore 312 (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, 1977), 190.

6 Birger A. Pearson, “Christians and Jews in First-Century Alexandria,” The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 79, No. 1/3 (Jan. – Jul. 1986), 209.

7 Theodor H. Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures (Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1976), 352.

8 Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures, 352.

9 Gaster, The Dead Sea Scriptures, 352.

10 In the Old World numerous varieties of trees were said to have been the identity of the World Tree or Tree of Life.

11 F. Kent Reilly, III, “Cosmos and Rulership: The Function of Olmec-style Symbols in Formative Period Mesoamerica,” in Visible Language, Vol. 24 (Winter 1990), 12-37.

12 J. Eric S. Thompson, Maya History and Religion (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 19976), 283-4.

13 Personal communication from Brian Stross, University of Texas at Austin, June 1997. This tradition was explained to Stross by the Tenejapa Tzeltales Maya of Mahosik while gathering information for his dissertation field research.

14 Bernardino de Sahagún, Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, ed. A. Lόpez Austin and J. Garcia Quintana, 2 vols. (Mexico: CNCA/Alianza Editorial Mexicana, 1989), bk. 6, ch. 30, I, 414; ch. 31, I, 415, cited in Lόpez Austin, Tamoanchan, Tlalocan: Places of Mist (Niwot, CO: University of Colorado, 1997), 250.

15 The Popol Vuh was the sacred book of the 16th century Quiché Maya. It was a narrative thought to be originally recorded in an illustrated Maya Codex. The Popol Vuh was copied in the Quiché language using the Latin alphabet by a Quiché scribe and subsequently copied and translated into Spanish.

16 Mary H. Preuss, Gods of the Popol Vuh (Culver City, California: Labyrinthos, 1988), 9.

17 Denis Tedlock, Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings (New York: A Touchstone Book published by Simon & Schuster, 1996), 39, 116, 139.

18 For a comparison of Hun Hunahpu in the Popol Vuh with Osiris of Egypt, see Diane E. Wirth, “Through Death Comes Life: The Dying and Ressecting Grain Gods of Mesoamerica and Egypt,” The Aesthetics of Enchantment in the Fine Arts, Analecta Husserliana, Vol. 65, Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka and Marlies Kronnegger, eds. (Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000).

19 Susan Tower Hollis The Ancient Egyptian “Tale of Two Brothers” (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1990), 124.

20 Suetonius, Domit., 15, and Alex. Lampridius, Alex. Sev., 60.4-5, cited in Gaster, The Dead Sea Scrolls, 352.

21 Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, gen. Ed. John W. Welch, Vol. 7, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, 2nd. ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., and Provo, Utah: F.A.R.M.S., 1988), 283-85. 6

22 See John Welch, “The Execution of Zemnarihah,” Reexploring the Book of Mormon, Ed. John Welch (Provo, Utah: F.A.R.M.S. and Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1992), 250-1.

23 Michel Graulich, Myths of Ancient Mexico, translated by Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano and Thelms Ortiz de Montellano (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), 63, 213.