Mapping Zarahemlas

Mapping Zarahemlas

by Neal Rappleye

A couple of years ago, I was working on writing a weekly historical/apologetic commentary of the Book of Mormon, following along with the Gospel doctrine lessons. I was cruising through 1 Nephi, until I got to the part where they arrive in the Promised Land. In order to proceed from there, I needed to decide which geographic model I would use for the remainder of the commentary. I had always just accepted a specific model in Mesoamerica, but had never really bothered to explore what anyone else had to say on the subject. At this time, though, I figured if I was going to stake my commentary on a particular model, I ought to make the effort to ensure it really was the best model out there, or at least that it was the one I really thought was the best. So, I decided to start exploring other models, and as I did I paid specific attention to the methods being employed.

Why are methods important?

Why did I focus on methods? Of course, anyone can look at dozens of Book of Mormon geography models. Some are pretty obviously less plausible than others. If I was going to make a reasonable judgment about which model was most accurate, I needed some standards or criteria by which to judge. Such guidelines, however, are not inherently obvious or objective—if they were, we would not have so many different models in the first place. Developing solid criteria for a model of any kind requires developing a method by which evidence can be interpreted.

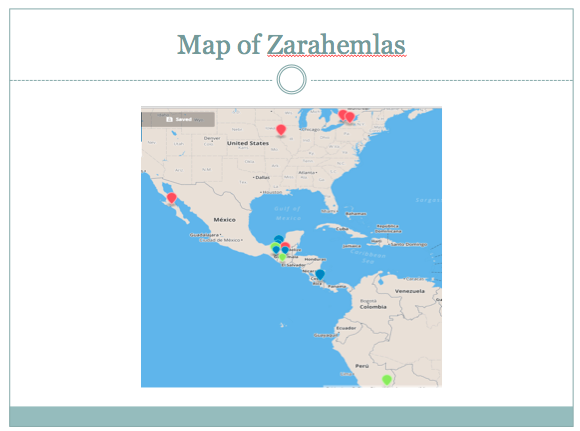

This map above shows a handful of different locations that have been proposed as Zarahemla just in the last 20 years (and this is not comprehensive). As you can see, the proposals are literally all over the map! Ranging from the Great Lakes to Peru, Zarahemla is everywhere! This is why methodology is important. I do not personally think this diversity of opinions is a problem of inconclusive evidence—I think it is a problem of methods. Wide methodological diversity leads to a diverse set of conclusions. Many proposals are being made without any notion of methodology at all; others have methodologies that ground the model, but the methods are not made explicit. Of the few who have discussed methods, many are too shallow, brief, and superficial, and several writers betray their methodological naïveté in the process. Often writers will offer their own methods, but not engage and critique the methods that others have used, or will construct straw man methods to knock down. To some extent or another, nearly everyone is guilty of not giving methodology due diligence.

I will not be advocating for any particular method—although I do have an opinion on the matter. Instead, I will be advocating for greater, more rigorous methodological discussion. While I do not expect to achieve a total consensus on every little issue in Book of Mormon geography, I do think considerable advancement can be made if we have greater open discussion about methods—everyone who wants to produce a geography, or critique one, ought to include a discussion of their methods, the methods of others, and why they favor the methods they do. Today I hope to facilitate such discussion by mapping out some of the patterns I have noticed in different methodologies and laying out some goals to help guide the discussion in a fruitful and productive direction.

Important Methodological Discussions

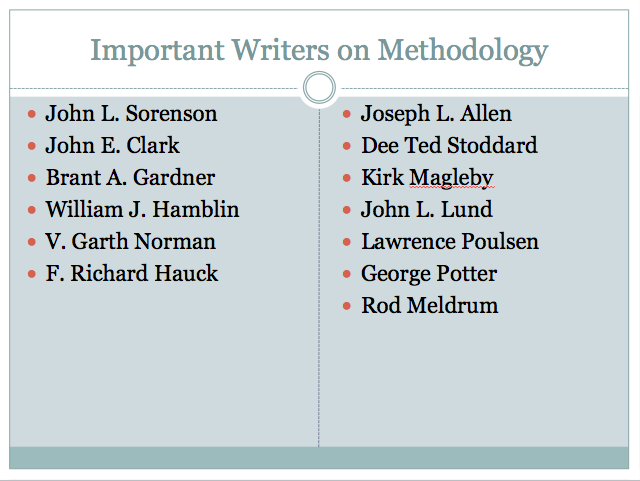

I would first like to start by highlighting a handful of writers who have produced important methodological discussions that anyone researching in Book of Mormon methodology ought to be aware of. As a disclaimer, I note that important is not a synonym for “good” or “quality”—some of these are, in my opinion, actually quite bad. But when there is an absence of rigorous debate on methods, bad methods can prevail and even become influential among lay persons who do not typically employ the critical thinking skills necessary to evaluate a proposed method and its accompanying model. As such, it is important to be aware of even very bad methods. So, the following is a short list those who have published important methodological discussions:

I'm sure there are others that could be included, but these are ones that everyone and anyone who writes on Book of Mormon geography should be aware of, and should be engaging.

Types of Methods

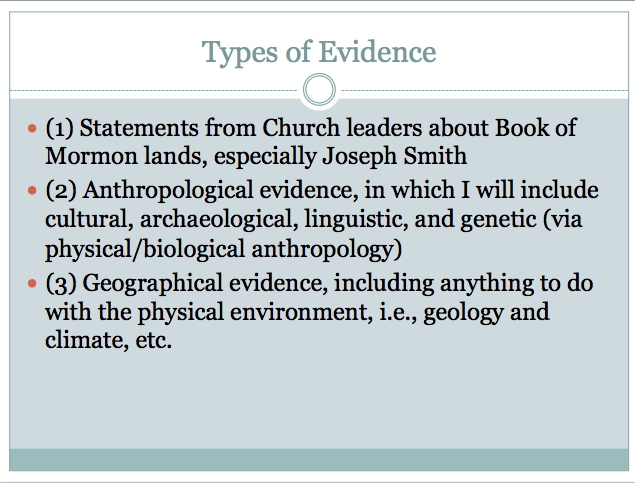

As I have reviewed various Book of Mormon geographies, I have noticed that there is generally three types of “evidence” which tends to get used: (1) statements from Church leaders about Book of Mormon lands, especially Joseph Smith; (2) anthropological evidence, in which I will include cultural, archaeological, linguistic, and genetic (via physical/biological anthropology); and (3) geographical evidence, including anything to do with the physical environment, i.e., geology and climate, etc.

Every author I have looked at uses some combination of these evidence types, giving different weight and priority to different kinds. What I am referring to when I speak of method is the process by which they assemble and give weight to each of these different evidences, including how they analyze and evaluate the evidence.

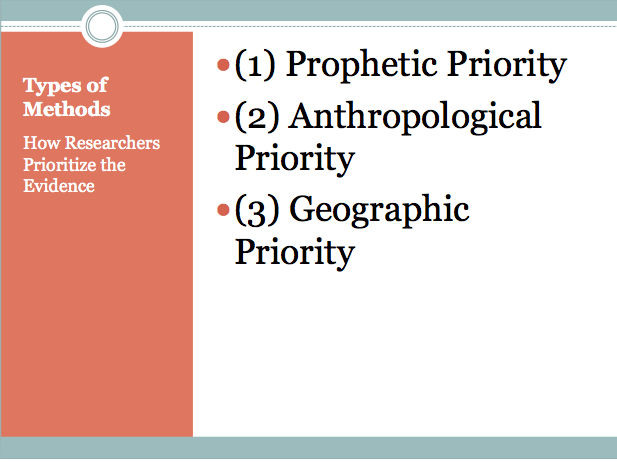

What I noticed is that authors tend to give priority to one of the three kinds of evidence, and that this choice of which evidence will be prioritized often determines where they situate Book of Mormon lands, at least in terms of general location, if not specifics. I thus began to use a threefold classification system for all of the different methods I was encountering:

These categories are of course somewhat idealized, and no one should make the mistake of thinking that because an author is categorized as using a “prophetic priority,” they therefore ignore the evidence from the other two groups. As I already mentioned, nearly all writers employ some combination of all three types of evidence. However, it is usually correct to say that how evidence in the other two categories is used and interpreted is often driven by the conclusions they reach based on the prioritized evidence. The three method types also should not be mistaken as merely three methods. There are several different “geographical priority” methods, for example, and some differ substantially in their approach. Nonetheless, I have found this categorization useful when comparing and contrasting different models and the methods used to construct them.

Out of the handful of I have already looked at, most fall into the geographic or prophetic priority camp, as I categorize them.

The anthropological priority has seemingly few disciples, . and this list is somewhat deceptive since Joseph and Blake Allen are co-authors, and Ted Stoddard is their editor. However, this is not comprehensive, and may not be representative, although it does seem that most battles going on today revolve around a geographic vs. prophetic dichotomy. I hope to continue to evaluate additional models and add to this list in the future

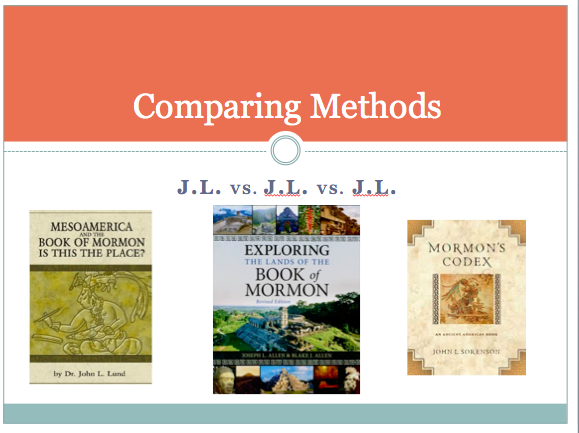

Comparing Examples of Each Approach: JL vs. JL vs. JL

To help you get a better idea of what I am talking about, I will provide a quick evaluation of the methods of three authors who are typically considered as leading experts: John L. Lund, Joseph L. Allen, and John L. Sorenson. My reason for choosing each of these three is that, at least if I have understood their methods correctly, they each represent one of the three different priorities, they are often considered leading experts on Book of Mormon geography, and I just thought it would be assuming to compare three different authors whose first and middle initials are JL.

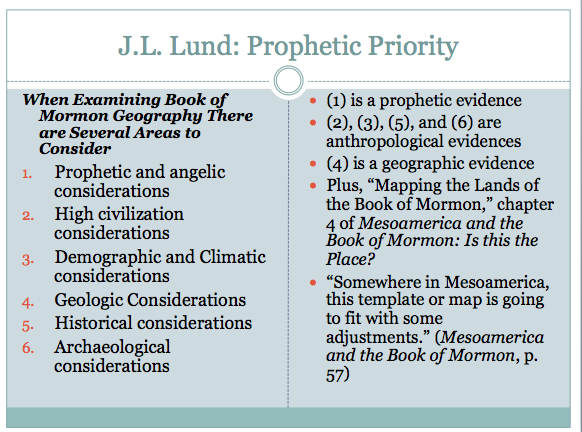

John L. Lund uses what I would consider an example of the prophetic priority method. In his book, MesoAmerica and the Book of Mormon: Is this the Place?, he explains:

In these areas of consideration, 1 is an example of prophetic evidence, 2–3, and 5–6 are examples anthropological evidences, and 4 is geographic. There is a chapter that does not fit squarely into these categories, chapter 4 on “Mapping the Lands of the Book of Mormon,” which comes after Lund has reviewed the Prophetic and Angelic considerations, but before he starts a chapter on “Evidences of High Civilization in Mesoamerica.” Other than that, the book presents evidences within each of these categories more or less in order.

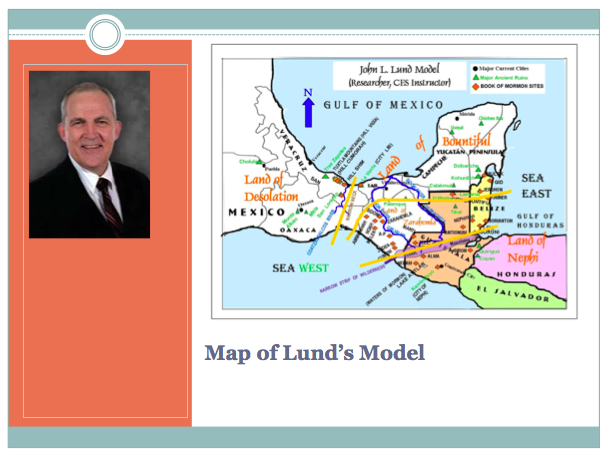

Lund clearly utilizes evidence from each category, but there can be little question that he places priority on prophetic evidence. It is the first evidence listed, and the first evidence he reviews. To that, it can be added that his follow-up volume, Joseph Smith and the Geography of the Book of Mormon, is dedicated to demonstrating that Joseph Smith authored the key evidence Lund uses in reconstructing his geography: The Times and Seasons articles published under Joseph Smith’s editorship.

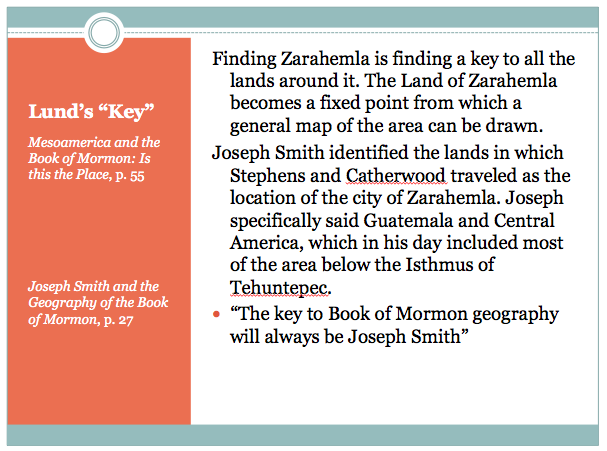

When talking about mapping the Book of Mormon, Lund makes this statement which I think is pretty revealing about his method. He starts the chapter off by quoting John E. Clark, who uses a geographic priority method essentially indistinguishable from Sorenson’s (discussed below). Instead of actually employing the internal map method as described by Clark and Sorenson, however, Lund explains: “Somewhere in Mesoamerica, this template or map is going to fit with some adjustments.”[1] Notice that at this stage, for Lund Mesoamerica is already a given. How did he get to this conclusion? The answer is he used statements from Joseph Smith’s Times and Seasons articles. He explains:

Finding Zarahemla is finding a key to all the lands around it. The Land of Zarahemla becomes a fixed point from which a general map of the area can be drawn. Joseph Smith identified the lands in which Stephens and Catherwood traveled as the location of the city of Zarahemla. Joseph specifically said Guatemala and Central America, which in his day included most of the area below the Isthmus of Tehuntepec.[1]

In his follow-up volume, Lund explains:

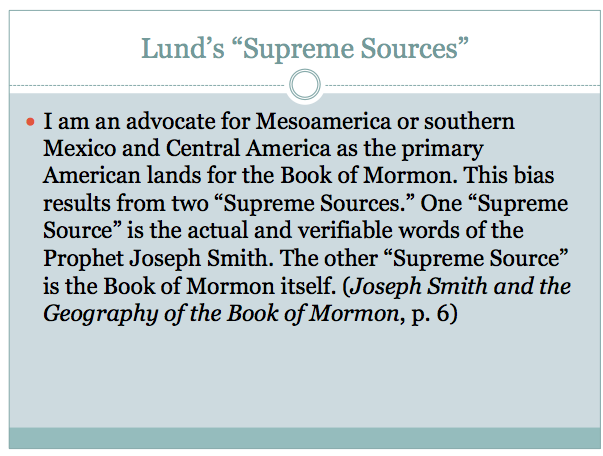

I am an advocate for Mesoamerica or southern Mexico and Central America as the primary American lands for the Book of Mormon. This bias results from two “Supreme Sources.” One “Supreme Source” is the actual and verifiable words of the Prophet Joseph Smith. The other “Supreme Source” is the Book of Mormon itself.[2]

While he identifies two “supreme sources,” as I read his work, I get the sense that for Lund, “The key to Book of Mormon geography will always be Joseph Smith,”[3] as he himself says.

Lund identifies 7 specific details of Book of Mormon geography which he argues were recognized by the prophet due to his visions of Nephite life and times between 1823–1827. These details form the primary basis for his maps of Book of Mormon lands, though he uses some geographic passages in the Book of Mormon to back them up. He explains that his maps were developed using “internal information given in the Book of Mormon plus the insights added by Joseph Smith.”[4] In my estimation, however, the “insights added by Joseph Smith” were the driving force in his configuration, and the geographic evidence played merely a supportive role. For example, Lund places the landing of Lehi in northern South America, on the basis of the declaration of in one Times and Seasons article that Lehi landed “a little south of the Isthmus of Darien,” which is Panama today. Lund then uses a unique interpretation of 1 Nephi 18:23–25 to argue that Lehi’s party traveled another 1100 miles, after landing, up to the area of present day Guatemala.

A potential exception to this is his use of ore deposits of gold, silver, and copper. This is, in my view, one of Lund’s more significant arguments (such geological considerations are generally ignored by other geographers, including Sorenson). Lund uses the presence and distribution of these ores to argue that only Mesoamerica can be lands of the Book of Mormon. Here, Lund makes a geographic-based argument as a means of establishing Mesoamerica as the exclusive region in which Book of Mormon events could take place. The geological evidence approaches a level of importance in Lund’s method near that of Joseph Smith’s words, as is evidence by the fact that he uses it again in his second book as his sole example of the Book of Mormon text as a “supreme source” on Book of Mormon geography. (While evidence from volcanism, another geological evidence, appears in the appendix.) Thus, in Lund’s use of geographic evidence, there is an emphasis on geological data.

Anthropological evidence is also used generally in a more supportive role. Having used Joseph Smith’s Times and Seasons articles and supporting passages from the Book of Mormon to establish Mesoamerica as the right place, most of the rest of his first book focuses on Lund’s view that historical and cultural evidence support this designation. He primarily uses historical, cultural, and religious information rather than correlating specific archaeological findings to Book of Mormon cities.

While I do not doubt that Lund would insist that it is the combination of all three lines of evidence—prophetic, geographic, and anthropological—which establishes Mesoamerica as “the place,” I would also be surprised if he were to deny that he places primary emphasis on the words of Joseph Smith.

J.L. Allen: Anthropological Priority

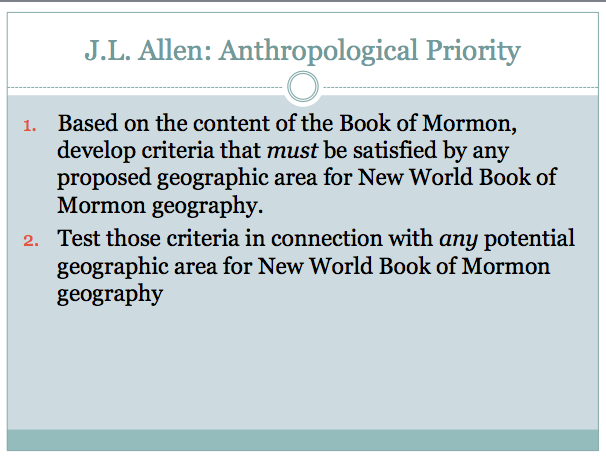

I would brand the Joseph L. Allen’s method as an anthropological priority. In an editorial preface to the revised edition of Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, co-written by his son Blake Allen, Ted Dee Stoddard, their editor, writes

The Allens’ approach to Book of Mormon geography is as follows:

- Based on the content of the Book of Mormon, develop criteria that must be satisfied by any proposed geographic area for New World Book of Mormon geography.

- Test those criteria in connection with any potential geographic area for New World Book of Mormon geography.[1]

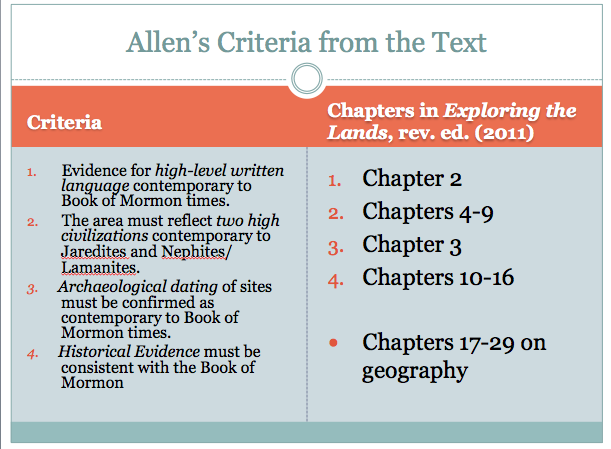

Stoddard also outlines the criteria developed by Allen

- Evidence for high-level written language contemporary to Book of Mormon times.

- The area must reflect two high civilizations contemporary to Jaredites and Nephites/Lamanites.

- Archaeological dating of sites must be confirmed as contemporary to Book of Mormon times.

- Historical Evidence must be consistent with the Book of Mormon.

Each of these four criteria are types of anthropological evidence. Looking at the table of contents in Allen’s book reveals that the book is structured according to these categories. After the introductory first chapter, chapter 2 discusses language (criteria 1); chapter 3 discusses chronology (criteria 3), chapters 4–9 discuss the archaeological record and correlates specific culture groups to the Jaredites, Nephites/Lamanites, and Mulekites (criteria 2); then, chapters 10–16 review the evidence from various Spanish and native chroniclers (criteria 4). Finally, after all of that, the Allen’s begin to layout their geographical model of Book of Mormon lands in chapters 17–29. As they finally get ready to discuss the geography, Joseph Allen writes:

My impression is that most students of Book of Mormon geography look first at the map and second at the cultural patterns of a given area. My approach has been just the reverse. I have seriously attempted first to understand the traditional history, the archaeological history, and the linguistic history of an area before attempting to establish a Book of Mormon geographical picture.

Only when I satisfied myself that Mesoamerica – and only Mesoamerica – fits the prescribed cultural, linguistic, archaeological, and traditional patterns required by the Book of Mormon did I then feel comfortable in attempting to propose a geographical picture in relation to the Book of Mormon.[1]

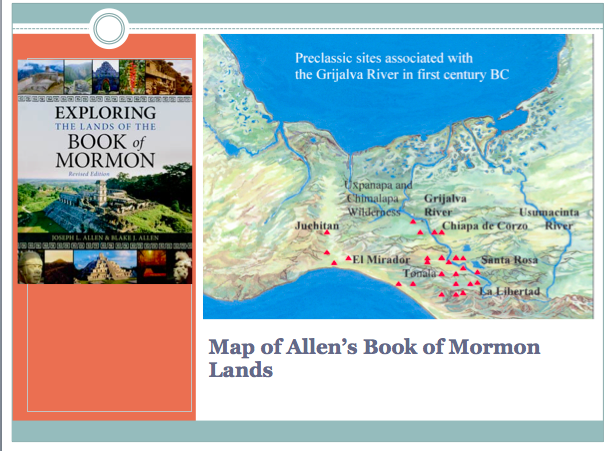

Earlier in the book, they explained, “Mesoamerica – and Mesoamerica only – fits the prescribed cultural, linguistic, archaeological, and traditional patterns required by the Book of Mormon itself. With that evidence in place we can make geographical proposals with a high level of confidence.”[1] Thus, the Allens emphatically insist that they placed priority on anthropological data.

A natural result is that the anthropological data influences their geographic correlations—after all, if the Olmec are identified as Jaredites, then Jaredite territory must be correlated with the lands where the Olmec lived. The Allens themselves acknowledge this aspect of their approach when talking about dates. “Dates in the Book of Mormon are precise, pervasive, and constantly associated with geographic locations. Dates, therefore, represent one clear marker that can help us understand and identify possible lands of the Book of Mormon.” (p. 82) Thus, while they have a long and extensive analysis of the geographic information in the text, and offer interpretations of it that fit the Mesoamerican landscape, both the choice of Mesoamerica, and the broad outlines of their model were determined first by their analysis of the anthropological data.

Prophetic evidence plays a minimal role in the development of their geography, with the Joseph Smith Times and Seasons articles occasionally getting mentioned, or the occasional use of a quote from another Church leader. The most extensive use of the Times and Seasons articles comes at the end of their “land southward” chapter, where they note that the ruins “which were proposed as possible Book of Mormon sites by Joseph Smith in the Times and Seasons, are in the area proposed as the land southward.” (p. 490) The FAQs section of this same chapter, they pose the question about whether or not Joseph Smith’s identification of Zarahemla, gives credibility to their proposed land southward, to which they offer some commentary on the Times and Seasons articles, a then reprint extracts from those articles, all of which suggests that they do think it gives their identification some credibility (pp. 491–492). But there is never an extended argument that such statements should be taken as definitive and serve as evidence for specific Book of Mormon locations (as with Lund), and in general they simply focus on geographic and anthropological evidence, with the latter taking priority.

J.L. Sorenson: Geographical Priority

John L. Sorenson has had the most to say about what he considers proper methods for developing a Book of Mormon map, and to truly get a sense for his method, I recommend you consult his works (the same, of course, goes for the above writers as well). Sorenson has made it indisputably clear that he places priority on geography itself. In his recent magnum opus, Mormon’s Codex, Sorenson states bluntly, “In order to have a realistic hope of establishing a real-world location for Book of Mormon events, one must reconcile everything the text says or implies about geography.”[1] This is merely a reiteration of what Sorenson has been arguing for decades prior to this time. In a 1994 lecture, Sorenson insisted, “It will do no good to find evidences in Alaska for the Nephites, if the Nephites were not in Alaska, anymore than to find evidence in Tibet. We need to be in the right place and in the right time period if we are going to use… archaeological evidences, or linguistic evidence.”[2] Thus, according to Sorenson, “Only when we have an idea of [the Geography] … can we know which historical traditions or archaeological sequences can be compared most usefully with Mormon’s text.”[3]

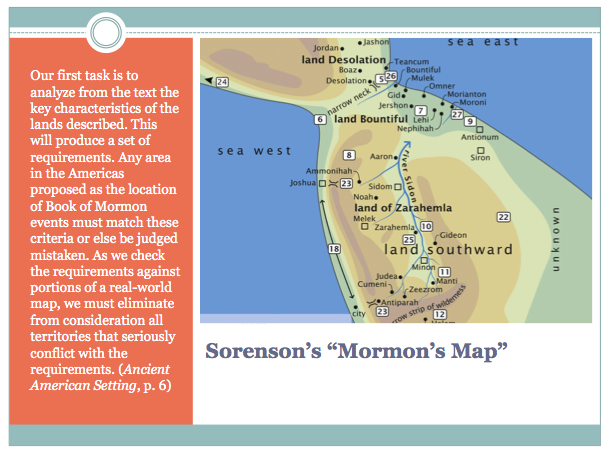

But how is one to collect and comprehensively use everything the text says about its geography? Sorenson’s way of doing that is to construct what he calls an “internal map,” without any reference to data outside the Book of Mormon itself:

Our first task is to analyze from the text the key characteristics of the lands described. This will produce a set of requirements. Any area in the Americas proposed as the location of Book of Mormon events must match these criteria or else be judged mistaken. As we check the requirements against portions of a real-world map, we must eliminate from consideration all territories that seriously conflict with the requirements.[4]

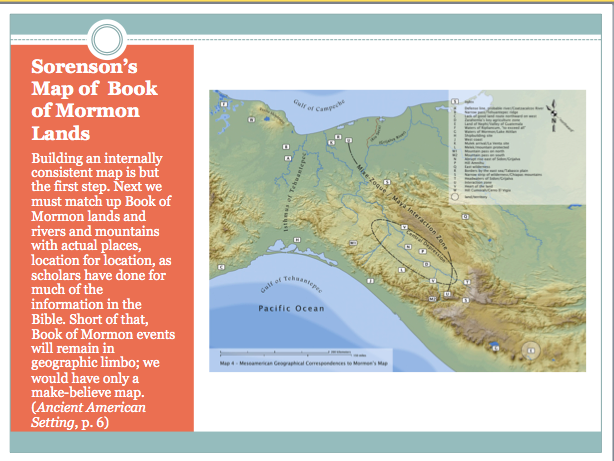

Sorenson has done this in his book Mormon’s Map [slide], and thus far his remains the most comprehensive internal analysis of the text to date. Sorenson argues that building such a map creates “a synthesis of the internal geographical data,”[5] which serves as a check on any geographic proposal. Sorenson goes on:

Building an internally consistent map is but the first step. Next we must match up Book of Mormon lands and rivers and mountains with actual places, location for location, as scholars have done for much of the information in the Bible. Short of that, Book of Mormon events will remain in geographic limbo; we would have only a make-believe map.[6]

Thus once you have a map giving a comprehensive picture of what can be known about Book of Mormon lands, the goal is then to see if it fits anywhere in the Americas. When Sorenson’s reconstruction is compared to the real world, only one location survives: Mesoamerica.[7]

However, the fit cannot quite be made on strictly geographical terms. The orientation of Mesoamerica requires what appears to be a skewing of directions. Sorenson has thus invoked anthropological evidence to argue that directions are cultural constructs that vary from one culture to another. Thus, at least one sort of anthropological evidence plays a crucial role in the development of Sorenson’s geography. After that, Sorenson proceeds to examine chorological sequences, cultural practices, historical trends, archaeological sites, etc. much like Allen does, only Sorenson’s choices of which cultures and archaeological sequences to follow was determined by the geographical correlation that he made.

I did notice one exception to Sorenson’s typical avoidance of prophetic evidence. Toward the end of Mormon’s Codex, when addressing how the plates got from Mexico to New York, Sorenson invokes the Prophet Joseph Smith.

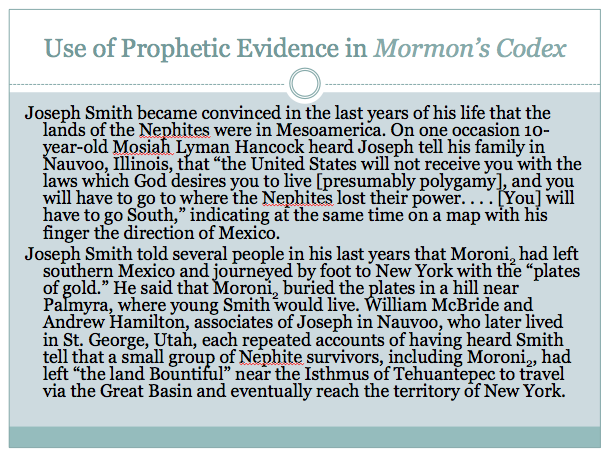

Joseph Smith became convinced in the last years of his life that the lands of the Nephites were in Mesoamerica. On one occasion 10-year-old Mosiah Lyman Hancock heard Joseph tell his family in Nauvoo, Illinois, that “the United States will not receive you with the laws which God desires you to live [presumably polygamy], and you will have to go to where the Nephites lost their power. . . . [You] will have to go South,” indicating at the same time on a map with his finger the direction of Mexico.

Joseph Smith told several people in his last years that Moroni2 had left southern Mexico and journeyed by foot to New York with the “plates of gold.” He said that Moroni2 buried the plates in a hill near Palmyra, where young Smith would live. William McBride and Andrew Hamilton, associates of Joseph in Nauvoo, who later lived in St. George, Utah, each repeated accounts of having heard Smith tell that a small group of Nephite survivors, including Moroni2, had left “the land Bountiful” near the Isthmus of Tehuantepec to travel via the Great Basin and eventually reach the territory of New York.[2]

While Sorenson never claims that these should be taken as revelatory statements that are binding to Book of Mormon geographers, he clearly is using them to support the idea that Moroni carried the plates from the site of the final battles in northern Mesoamerica to the hill in New York where they were found.

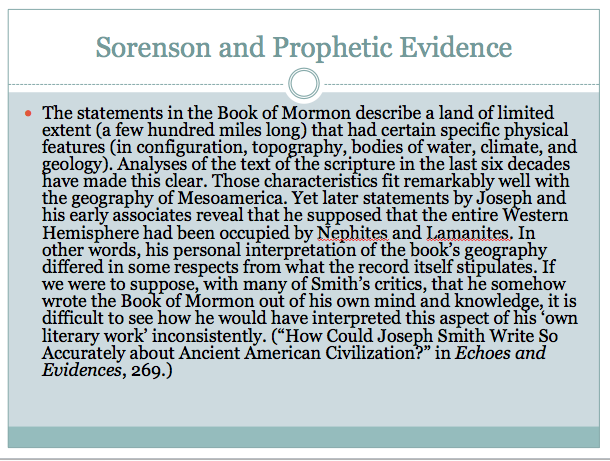

Sorenson does not make extensive use of prophetic evidence, and has generally eschewed such arguments, insisting that there are no genuinely prophetic/revelatory statements to use. Sorenson does not completely avoid using such evidence, however. He does tend to use it very differently, however. Instead of using what Joseph Smith said to validate his model, he openly admits that it contradicts his model, but then uses that as evidence that Joseph Smith could not be the author of the Book of Mormon. Sorenson writes,

The statements in the Book of Mormon describe a land of limited extent (a few hundred miles long) that had certain specific physical features (in configuration, topography, bodies of water, climate, and geology). Analyses of the text of the scripture in the last six decades have made this clear. Those characteristics fit remarkably well with the geography of Mesoamerica. Yet later statements by Joseph and his early associates reveal that he supposed that the entire Western Hemisphere had been occupied by Nephites and Lamanites. In other words, his personal interpretation of the book’s geography differed in some respects from what the record itself stipulates. If we were to suppose, with many of Smith’s critics, that he somehow wrote the Book of Mormon out of his own mind and knowledge, it is difficult to see how he would have interpreted this aspect of his ‘own literary work’ inconsistently.[1]

What Does All This Mean?

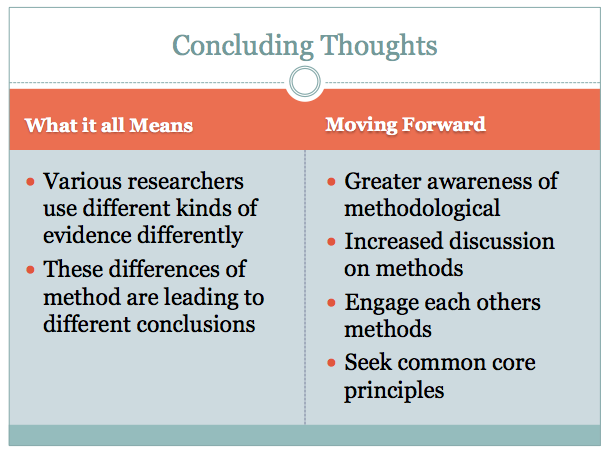

Clearly, between Lund, Allen, and Sorenson, we find all three types of evidence being used a variety of different ways. While each of these authors came to the conclusion that Mesoamerica is the right place using a different priority, their actual models differ in a number of ways, as any careful examination will reveal. What’s more, these conclusions are being disputed by others using the same classes of evidence. Rod Meldrum, for example, employs a type of “prophetic priority” method, with emphasis on the words of Joseph Smith, and yet comes to dramatically different conclusions than Lund, placing the Book of Mormon in the Eastern United States. George Potter, meanwhile, employs an anthropological method not too different from Allen’s, and yet builds his model in Peru rather than Mesoamerica. Numerous other examples could be given demonstrating how this methodological free-for-all is contributing to confusion on the topic of Book of Mormon geography.

How Do We Move Forward?

So, what can we do about this problem? How can we move forward? To some extent, nothing. There are always going to be those who ignore serious work on the topic and think up some wild and random theory about the Gulf of Mexico being raised up, or some up chunk of water be sunk down, before the destruction around the crucifixion of Christ. What is more, even among those who do serious work, we cannot compel anyone to agree with a specific method. The views of researchers like Lund, Allen, and Sorenson, and several others, have been developed overtime and through extensive research. They are not likely to all three go to lunch together and then come back in agreement on how to approach Book of Mormon geography. So how do we move forward?

I propose that we start having greater open discussion and debate about methods. All those who consider themselves serious scholars should, if they have not already, reflect on the methods they use, and write out an article explaining them; or include a chapter explaining them in their books. They should also look at the methods others are employing and engage those methods with cogent criticisms. Some of this has already taken place; but I suggest it needs to be much more frequent and common. There should be back-and-forth on methods dialogue, with responses to critiques given, and so on. These discussions will not produce any kind of consensus quickly. They will help every individual researcher be more aware of their own methods, sharpen those methods as they defend them from criticisms, even revise those methods should fatal defects be exposed, and potentially persuade others who are only starting out, such as myself, to employ their methods. It will also create an environment where sloppy or weak methods will wither away more quickly.

To facilitate this process, I would like to propose that a volume collecting essays on methodology—some of the most important essays already available, along with all new papers as well—which could then become a foundation for future discussion going forward. A go-to-source, if you will, for scholars just beginning to enter the field, to help them get oriented to the methodological state of affairs and begin thinking critically about their own methods, and for long time researchers to use as a reference in future discussion. I volunteer to overseer the editing and production of such a volume, and invite all interested scholars to contact me about contributing—consider this a formal call for papers. While it is doubtful there will ever be a completely unanimous method followed, such is not necessarily desirable. To some extent, methodological pluralism is a virtue. However, I do believe that in the course of time, we could see broad agreement on at least some core principles upon which all methods can be based. The first-step, in my estimation, should be to work toward settling the issue of which evidence should have priority—geographic, archaeological, or prophetic? Simply reaching a degree of consensus on that would go a long way to reducing overall disagreements.

Thank you.

[1] Lund, Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon, 55.

[2] Lund, Joseph Smith and the Geography of the Book of Mormon, 6.

[3] Lund, Joseph Smith and the Geography of the Book of Mormon, 27.

[4] Lund, Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon, 57, emphasis mine.

[1] Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 17, emphasis in original. Cf. Sorenson, Geography of Book of Mormon Events, 210: “We need instead to use the entire scripture, without exception…. We must understand, interpret and deal successfully with every statement in the text, not just what is convenient or interesting to us.” (emphasis in original).

[2] Sorenson, “The Book of Mormon in Ancient America,” 6.

[3] Sorenson, Images of Ancient America, 188.

[4] Sorenson, Ancient American Setting, 6. For a listing of all the criteria Sorenson has found in the text, see Sorenson, Geography of Book of Mormon Events, 357-364. For the reasoning behind these criteria, see pp. 215-353.

[5] Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 120.

[6] Sorenson, Ancient American Setting, 6.

[7] See Sorenson, Ancient American Setting, 1-48; Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 17-23, 119-143.