Quetzalcoatl, White Gods, and the Book of Mormon

Quetzalcoatl, White Gods, and the Book of Mormon

by Brant A. Gardner

First publshed in the blog Rational Faiths, Jan. 2014

Part I: Skin Color

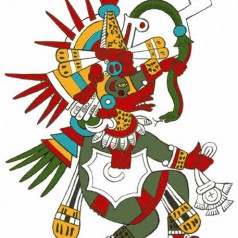

The Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl has entered public consciousness as the “white god.” The very fact that a Native American people would have a bearded Caucasian deity has led to widespread speculation about who might have been the real person about whom the legends developed. The earliest speculation came from some of the Spanish priests who first encountered Aztec religion. They believed that the original bearded Caucasian must have been St. Thomas the wandering Apostle. Other suggestions have been St. Bernard and Ethan Smith, who published his View of the Hebrews in 1823, suggested that it was Moses.

The LDS speculation has associated the Quetzalcoatl legends with the appearance of the resurrected Christ to the people gathered in Bountiful as recorded in the Book of Mormon. No less a figure than Church president John Taylor, wrote of Quetzalcoatl:

“The story of the life of the Mexican divinity, Quetzalcoatl, closely resembles that of the Savior; so closely, indeed, that we can come to no other conclusion than that Quetzalcoatl and Christ are the same being. But the history of the former has been handed down to us through an impure Lamanitish source, which has sadly disfigured and perverted the original incidents and teachings of the Savior’s life and ministry.”1

President Taylor’s statement recognizes that the Quetzalcoatl legends do not really match what we see in the Book of Mormon, but ascribes those differences to the impure source and time. President Taylor is absolutely correct that over time stories can develop, evolve, and shift away from their original sources. That is actually a perfect description of what has happened to the stories about Quetzalcoatl. However, rather than drift away from the Book of Mormon story of Christ’s appearance into a paganized retelling, they stories have drifted from a pagan story into a Christianized one. The LDS correlation between Quetzalcoatl is more than just a similar attempt to find the bearded Caucasian that we first saw among the Spanish priests, it is based upon the stories that the Spanish priests used to declare that bearded Caucasian as St. Thomas. Unfortunately, while those stories were based on the native deity Quetzalcoatl, they had already been warped into new forms as the Spanish fathers recorded them.

The entire history of the development of Quetzalcoatl stories from native deity to some Christian reformer is one of assumptions modifying data into forms closer to the assumptions. When we do the historical footwork to pull apart the threads of the tapestry, all of the elements of the story that make the bearded Caucasian appear to be Christian are only distortions of the native story—including the idea that Quetzalcoatl was a bearded Caucasian.

How was Quetzalcoatl White? Quetzalcoatl’s statue was always painted black. The artistic representations had visual signals to show that it was Quetzalcoatl (parallel to keys on a ring declaring which figure in a Renaissance painting was Peter). The only time he was “white” was when he was described with his association with the East, which was associated with the color white just as other directions were associated with red, black, and yellow.

Anthropologists Mary Miller and Karl Taube explain the color associations of the Mesoamerican directions:

“The identification of colors with directions is most fully documented among the ancient Maya, who had specific glyphs for the colors red, white, black, yellow, and green. In the Yucatec Maya codices, these colors are associated with east, north, west, south and center, respectively. . . . Like the Maya, Central Mexicans appear to have identified white with the north and yellow with the south.”2

Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas records an unfortunately abbreviated version of the four sons of a heavenly god and goddess, the four Tezcatlipocas. Only two give their particular colors, and Quetzalcoatl is not one of them:

This god and goddess engendered four sons:

The oldest they named Tlatlauhqui Tezcatlipoca, and those of Huexotzinco and Tlaxcala, who held this one to be their principal god, called him Camaxtle: This one was born all red.

They had the second son, whom they called Yayauhqui Tezcatlipoca, who was the best and the worst, and he was more powerful and able than the other three, because he was born in the middle of all: this one was born black.

The third was called Quetzalcoatl, and as another name, Yohualli Ehecatl.

The fourth and smallest was called Omitecutli and by another name, Maquizcoatl and the Mexicans [Aztecs] called him Huitzilopochtli, because he was left-handed. He was held by the Mexicans [Aztecs] to be their principal god.3

We see the pattern, although Quetzalcoatl is not specifically linked to the color. Nevertheless, the Aztec perception was that Quetzalcoatl was white only in the same way that Tlatlauhqui Tezcatlipoca was red and Yayauhqui Tezcatlipoca was black. It was their association with a direction that made the determination, not their skin color.

The Aztecs really didn’t see that big of a difference between their skin color and that of the Spanish. Miguel León-Portilla, professor emeritus at the Institute for Historical Research, National University of Mexico, quotes Alvarado Tezozomoc, a native nobleman (who wrote no earlier than 1609, a date found in the manuscript “Mexican [Aztec] Chronicle”): “Their [Spaniards’] skin is very white, more so than ours.”4

Quetzalcoatl became Caucasian because the Spanish fathers recording the tales couldn’t conceive of the association with a direction and assumed that the description must have depicted skin color. It was part of a transformation of native legend that they made into a prediction that the Spanish would come and rule.

Part II: Beards, Virgin Birth, and Preaching Christian Principles

What about the Beard? A distinguishing physical contrast between the natives and Spaniards was the natives’ relative beardlessness. A bearded god might therefore be considered unusual. In modern versions of the Quetzalcoatl tale, the beard is one of the most frequent indicators suggesting that Quetzalcoatl must have been foreign.5Sahagún’s sixteenth-century informants say, “His beard was long, exceedingly long. He was heavily bearded.”6 So well-known was this element that, by 1615, Fray Juan de Torquemada could state: “This was held as very certain, that he was of good disposition . . . bearded. . . . ”7

The sources report a variety of beard colors: to Torquemada, blond; to Bartolomé de Las Casas (a Dominican priest, died 1566) black; and to Diego de Durán, red and graying.8 Such variations probably signal that the color was not part of pre-conquest lore. Nevertheless, beards really were part of the pre-conquest Mesoamerican religious tradition and are frequently depicted in pre-conquest Mesoamerican art. However, these same native depictions prove that, while there was a native emphasis on bearded figures, the beard was not unique to Quetzalcoatl and is not even diagnostic for Quetzalcoatl, meaning that Quetzalcoatl may be painted and recognized without a beard.

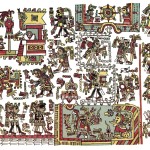

Not only could Quetzalcoatl be represented without a beard, other deities could wear them. The Codex Nuttall, reportedly sent to Spain in 1519, had been composed in the Mixtec culture of Central Mexico at an unknown date prior to the conquest. It shows several bearded figures: male 13 Reed, male 1 Death, male 4 Jaguar, male 10 Rain, and male 10 Grass. Male 9 Wind, the name attached to the figure who is painted with the iconography identifying Quetzalcoatl (named male 9 Wind in Mixtec codices), is not bearded. Therefore, in the Codex Nuttall, beards are certainly part of the iconographic representations of various figures, but not for male 9 Wind.9

Two companion codices were painted for the Spanish after the conquest. They use more Western artistic conventions, but the layout and content are native. Both cover the same information in the same order, but one has two sections that are not in the other. They are known as the Codex Telleriano-Remensis and the Codex Ríos. The Telleriano-Remensis contains the date of 1563 and the Ríos 1566, so they were painted no earlier than those dates.10 In spite of being post-conquest productions, they appear to contain pre-conquest information in their painting along with the obviously post-conquest glosses (one written in Spanish and one in Italian).

The Telleriano-Remensis has two drawings of figures that can be identified as Quetzalcoatl. One is actually labeled “Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl” in Spanish. Neither representation of Quetzalcoatl is bearded. The Codex Ríos shows one depiction of Quetzalcoatl for which there is no analog in the Telleriano-Remensis. In that drawing, a bearded Quetzalcoatl is on top of a pyramid, wearing a long cape with a pattern of crosses on the fabric.11

Not only is the beard itself more widespread than popular designations of the “bearded white god” would suggest, but there are also indications that Mesoamericans sometimes used false beards. The Annals of Cuauhtitlan (originally written in Nahuatl, probably ca. 1545–5512 ) describes Quetzalcoatl at Tula: “Immediately he made him his green mask; he took red color with which he made the lips russet; he took yellow to make the facade; and he made the fangs; continuing, he made his beard of feathers.”13The Codex Borgia, an undated, but pre-conquest, document from Central Mexico, shows Quetzalcoatl on plates 56 and 73, masked and wearing a beard of what appears to be yellow feathers.14

Native deities could have beards, but they might be feather beards. Of course, when the Spanish priests told the story, things changed and feather beards were always real beards. Just as they took the white direction and made it Caucasian skin, they took a typical symbolic beard seen many deities and made it a remarkable beard only on one of them.

Wasn’t Quetzalcoatl Born of A Virgin, as Was Jesus? The association between a virgin birth and Christianity was, unsurprisingly, important for the early Spanish writers. Father Gerónimo de Mendieta (1525–1604), a Franciscan missionary, reports a conversation between a Spanish priest and an old Indian about an indigenous sacred book:

And when this priest asked the Indian what the book contained of his doctrine, he did not know how to reply in particular, but from what he responded, if that book had not been lost, [the priest] would have seen how the doctrine which he taught and preached to them and that destruction which the book contained were the same. . . . Also he said that they knew of the by the flood. . . . They knew also of the mission of the angel to Our Lady, by a metaphor, saying that a very small object like a feather fell from the heavens, and a virgin picked it up and placed it over her womb whereupon she became pregnant.15

Aztec mythology appears to have a category of miraculous births that post-contact authors have labeled “virgin births.” In Aztec mythology, however, the virgin birth was not Quetzlcoatl’s story, but rather Huitzilopochtli’s. The particular tale that Mendieta related describes the birth of the Aztec tribal deity Huitzilopochtli, not any version of Quetzalcoatl. That tale is reported by Sahagún’s informants:

To Uitzilopochtli [Huitzilopochtli] the Mexicans paid great honor.

Thus did they believe of his beginning, his origin. At Coatepec [serpent mountain place], near Tula, there dwelt one day, there lived a woman named Coatl icue [“serpent her-skirt”], mother of the Centzonhuitznaua [the four hundred Huitznahua]. And their elder sister was named Coyolxauhqui.

And this Coatl icue used to perform penances there; she used to sweep; she used to take care of the sweeping. Thus she used to perform penances at Coatepec. And once, when Coatl icue was sweeping, feathers descended upon her—what was like a ball of feathers. Then Coatl icue snatched them up; she placed them at her waist. And when she had swept, then she would have taken the feathers which she had put at her waist. She found nothing. Thereupon by means of them Coatl icue conceived.16

There was a virgin birth story, but it was a stretch to correlate it with the New Testament and it did not describe Quetzalcoatl but rather a different deity. That little detail became lost in the retelling.

Didn’t Quetzalcoatl Preach Christian Principles? A passage attributed to Andrés de Olmos illustrates the standard version of Quetzalcoatl’s religion: “He never admitted sacrifices of the blood of humans nor of animal, but rather only of bread and roses, flowers and perfumes, and of odors. [Also] he watched and prohibited with much efficacy wars, thefts, murders and other harms which they did to each other. Whenever wars were mentioned before him, or other evils concerning the wrongs of men, he would turn his face and cover his ears so that he would neither see nor hear them.”17 There are elements of this description that can be traced to native tales, but those native stories have already been modified in de Olmos’s description. The Histoyre du Méchique provides a more native version of Quetzalcoatl’s conflict with his brothers:

[Quetzalcoatl’s brothers] returned to look for Quetzalcoatl and they made him believe that his father had been changed into a rock, persuading him also that he sacrifice and offer something to this rock, such as lions, tigers, eagles, little animals, butterflies, for he would not be able to find these animals. And as he did not wish to obey them, they wanted to kill him, but he escaped from among them and climbed a tree, or something like it, on top of that same rock and shot arrows at them and killed them all. Having done this, others came seeking him with honors and they took the heads of his brothers and emptied the skulls to make drinking cups.18

The parallel text from Leyenda de los Soles involves his uncles, but the details clearly present a variant of the same story:

Now, Ce Acatl’s uncles, who are of the four hundred Mixcoa, absolutely hated his father, and they killed him.

And when they had killed him, they went and put him in the sand. . . .

Then his uncles are furious, and off they go, Apanecatl in the lead, climbing quickly.

But Ce Acatl rose up and broke his head with a burnished pot, and he came tumbling down.

Then he seizes Zolton and Cuilton. Then the animals blow [on the fire]. Then they sacrifice them.

They cover them with hot pepper, cut up their flesh a little. And after they’ve tortured them, they cut open their breasts.19

This is a far cry from the Quetzalcoatl who covered his eyes and ears so as not to be reminded of death.

Part III: What About the Prophecy of Quetzalcoatl’s Return?

As with “white” and “bearded,” the idea that Quetzalcoatl promised to return is an indelible aspect of the modern version of the tale. It is part of what we all know and is typically referenced without documentation. Also similarly to “white” and “bearded,” this well-known aspect of the tale is problematic. When B. H. Nicholson summarized the basic Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl tale he made no reconstruction of a promise to return. I agree with his reconstruction. It is absolutely certain that the original lore contained a section on Quetzalcoatl’s departure, but the corresponding promise to return is absent from all but one native source. That one reference is problematic. Rather, the promise to return is inextricably connected to Spanish accounts.

Those accounts begin at the very beginning of the Spanish presence in the New World. When Cortés entered the capital city of the Aztecs, Tenochtitlan,20 he made one of the most remarkable and fateful meetings of cultures in the history of the World. For the first time, a representative of a European nation met the ruler of the largest political domain in the New World. It was not only an encounter of cultures but also an encounter of languages. Cortés spoke no Nahuatl. Motecuhzoma (Anglicized to Montezuma)21 spoke no Spanish. A Spaniard who had been captured by and lived with the Maya, spoke Maya to an native woman, known as Marina,22 apparently a native speaker of Nahuatl who was sold to a Maya village after a family misfortune. Marina translated from Maya into Nahuatl. In this monumental meeting of cultures, communications between the two important figures went through two different translators and three languages.

Cortés indicates no difficulty with communication. In fact, he is very clear about the content of this meeting. In a letter written in 1520 to the king of Spain (published in 1522), he “quotes” Motecuhzoma’s welcoming speech:

For a long time we have known from the writings of our ancestors that neither I [Motecuhzoma], nor any of those who dwell in this land, are natives of it, but foreigners who came from a very distant land and likewise we know that a chieftain, of whom they were all vassals, brought our people to this region. And he returned to his native land and after many years came again, by which time all those who had remained were married to native women and had built up the villages and raised children. And when he wished to lead them away again they would not go, nor even admit him as their chief; and so he departed. And we have always held that those who descended from him would come and conquer this land and take us as their vassals. So because of the place from which you claim to come, namely from where the sun rises, and the thing you tell us of the great Lord or king who sent you here, we believe and are certain that his is our natural Lord, especially as you say that he has known of us for some time.23

This passage is remarkable—perhaps too remarkable, considering the number of translations Motecuhzoma’s words endured before reaching Cortés and the passage of nearly a year before the speech was recorded. A. R. Pagden, professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, comments on its doubtful authenticity: “Both this speech and the one that follows would seem to be apocryphal. Motecuhzoma could never have held the views with which Cortés accredits him. Eulalia Guzmán, a Mexican anthropologist (1890–1985), has pointed out the biblical tone of both these passages and how their phraseology reflects the language of the Siete Partidas [law code of Alfonso X24]. Cortés is casting Motecuhzoma into the role of a 16th Century Spaniard welcoming his ‘natural [divinely appointed] Lord,’ who in this case has been accredited with a vaguely Messianic past.”25 Pagden suggests that a similar tale seems to have been current in the native culture but that it was probably not faithfully reproduced in this record.26

Furthermore, Cortés’s description does not fit the Quetzalcoatl motifs. In Cortés’s report, a foreign leader brings his people to this land. They intermarry; and when he asks them to leave, they refuse. None of these elements matches the Quetzalcoatl lore, although there are points of similarity. However, the result of seeing the Spanish as foreordained to conquer Mexico was so effective that this story of a returning god was spread wherever the Spanish entered new territory. Historian Jacques Lafaye comments: “The prophecy of Quetzalcoatl was a specific Mexican instance of a belief common to the majority of the Indian peoples, the belief that men from the East would come to dominate them. Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca heard of it during his trek across the Southwest; Gómara cites it for Española; the Chibchas, the Tupi of Brazil, the Guaraní of Paraguay, had similar beliefs. In different regions of the New World the Spaniards were taken for ‘Children of the Sun.’”27 Such a widespread pattern indicates either a pan-American myth28 or a Spanish convenience, justifying their arrival and conquests. Although I have not done serious work on the myth of the other native peoples throughout South America, it seems more reasonable to me that the Spanish brought the myth with them, rather than discovering it in virtually the same form all of these diverse locales.

The purpose of Quetzalcoatl’s return as it appears in most sources is a prediction of theSpaniards’ arrival—which is not the same thing as predicting Quetzalcoatl’s return. As the return motif became increasingly Hispanicized, it more strongly justified the conquest—even its excesses. By a.d. 1579–81 when Diego de Durán composed his history, he has Quetzalcoatl instructing his people before his departure:

. . . and delivering to them [of Tula] a large discourse, he prophesied the coming of a strange people from the Eastern parts who would land in this place, with strange clothes of different colors, dressed from head to foot, and with coverings on their heads, and that this punishment was to be sent them from God in payment of the poor treatment which they had given him, and the agony he had suffered. With this great punishment, small and large would perish, not being able to escape from the hands of these his sons; that they were to come to destroy them, even though they were to hide in caves and in the caverns of the earth, and from there they would be taken and there they would go to persecute and kill these people.29

After the conquest, Cortés injects a new element into the native mythic consciousness. The remarkable arrival of strange men from the East was predicted, inevitable, and destined to overthrow the Mesoamerican world order. This Spanish mutation of the myth was so strongly attached to the political motives and historical reality of the conquest that it eventually fed back to the natives themselves, as witnessed by Sahagún’s informants. Nevertheless, the particular forms of the myth that are visible in the literature demonstrate that they are additions made through the influence of the clash of cultures that was the conquest of New Spain.

However, this element of the tale is post-conquest and cannot be reconstructed as an element of the pre-Columbian version of the tale. Therefore, it cannot have any relationship to the Savior’s promise of his second coming.

Summary: there are many more elements of the Quetzalcoatl story that are modified into more Christian forms. They can be reconstructed to show where they had some similarities to the native stories, but in all of them, as in these examples, the native story is quite foreign. What has happened is that some of the early Spanish priests put a more Christian spin on the stories. Unfortunately, when we look at the LDS authors who repeat the Quetzalcoatl stories, it is the Spanish fathers they quote and not the more native records.

Quetzalcoatl might appear to be a remembrance of Christ, but only because LDS authors have put their own spin on the story that the Spanish fathers had already spun into Christian gold from native Aztec straw.

Notes:

1John Taylor, Mediation and Atonement (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1882), 201, on GospeLink 2001, CD-ROM (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000).

2Miller and Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, 65.

3Garibay K., Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas, 23–24; translation mine.

4Miguel León-Portilla, Visiones de los Vencidos (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1972), 12; translation mine.

5Hunter, Christ in Ancient America, 17; Cheesman, The World of the Book of Mormon,30; Clark V. Johnson, “Prophetic Decree and Ancient Histories Tell the Story of America,” in Jacob through Words of Mormon: To Learn with Joy, edited by Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, Utah: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1990), 133.

6Sahagún, Florentine Codex, 3:13.

7Juan de Torquemada, Monarquía Indiana, 3 vols. (Mexico City: Editorial Sálvador Chávez Hayhoe, 1943), 2:255.

8Ibid., 1:255; Bartólome de Las Casas, Apologética Historia Sumaria, edited by Edmundo O’Gorman, 2 vols. (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1967), 1:644; Diego de Durán, Historia de las Indias de Nueva España, edited by Ángel María Garibay K., 2 vols. (Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 1967), 1:9.

9Zelia Nuttall, ed., Codex Nuttall (New York: Dover Publications, 1975). For male 13 Reed, see p. 7; male 1 Death, p. 10; male 4 Jaguar, p. 14; male 10 Rain, p. 14; male 10 Grass, p. 15; and male 9 Wind, p. 15.

10Nicholson, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, 61–62.

11“Codex Telleriano-Remensis,” in Antigüedades de México: Basadas en la recopilación de Lord Kingsborough, analysis and interpretation by José Corona Nuñez, 4 vols. (Mexico City: Secretaria de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1964), 1:180 [11 in Ms], and 1:187 [10 in Ms]. See also “Codex Ríos,” in Antigüedades de México: Basadas en la recopilación de Lord Kingsborough, analysis and interpretation by José Corona Nuñez, 4 vols. (Mexico City: Secretaria de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1964), 3:29 [Vol. 7 in the manuscript].

12Nicholson, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, 39.

13“Anales de Cuauhtitlan,” in Códice Chimalpopoca, edited by Primo Feliciano Velázquez (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1975), 9; translation mine. Bierhorst, History and Mythology of the Aztecs, 32–33, has a different translation directly from the Nahuatl text: “And so he did it, this featherworker, this Coyotlinahual. First he made Quetzalcoatl’s head fan. Then he fashioned his turquoise mask, taking yellow to make the front, red to color the bill. Then he gave him his serpent teeth and made him his beard, covering him below with cotinga and roseate spoonbill feathers.

14Gisele Díaz and Alan Rogers, eds., The Codex Borgia (New York: Dover Publications, 1993), 22, 5.

15Gerónimo de Mendieta, Historia Eclesiástica Indiana, 4 vols., (Mexico City: Editorial Sálvador Chávez Hayhoe, 1945), 1:538; translation mine.

16Sahagún, Florentine Codex, 1:1–2.

17The ascription to Olmos is made because of the similar passages in three later histories that appear to have had access to Olmos’s work. Slightly differing versions of this passage occur in Las Casas, Apologética Historia Sumaria, 1:644; Torquemada,Monarquía Indiana, 2:50; and Mendieta, Historia Eclesiástica Indiana, 92.

18Garibay K., Histoyre du Méchique, 113–4; translation mine.

19Bierhorst, History and Mythology of the Aztecs, 154

20Modern Mexico City was built on the site of Tenochtitlan. When Cortés arrived, the city occupied an island in a large lake. Bridges provided the only access, sections of which could be removed to improve the city’s defenses. The lake has since been drained and the entire area is occupied by the modern city.

21The name of this important Aztec king is spelled in several ways, attempting to approximate the Nahuatl pronunciation. A rendition that may be closer to the Nahuatl would be Mo-tekw-soma. The unvoiced w (w) creates the transliteration problems.

22Hugh Thomas, Conquest: Montezuma, Cortés, and the Fall of Old Mexico (New York: Touchstone Books, 1995), 172.

23Hernan Cortés, Letters from Mexico, translated by A. R. Pagden (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971), 85–86.

24Written between 1251 and 1265, the Siete Partidas are the law code of Alfonso X, “el Sabio” (the wise). It is “generally considered the most important law code of the Middle Ages (and largest legislative compilation since Roman times).” Suzanne H. Peterson, “The Legislative Works of Alfonso X, el sabio,” http://faculty.washington.edu/petersen/alfonso/lawtrans.htm (accessed May 2007).

25Cortés, Letters from Mexico, 467

26Ibid., 467. Thomas, Conquest, 406, exercises a similar caution: “Whether the myth of Quetzalcoatl, or Tezcatlipoca, or any other deity, did or did not exercise a decisive influence over Montezuma’s judgments we may never know. But he was exceptionally superstitious, even for a Mexican. He certainly seems, at the very least for a time, to have toyed with the idea of identifying Cortés with a lost lord who vanished into the east. But this identification did not necessarily implicate Quetzalcoatl.”

27Lafaye, Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe, 151.

28This appears to be the position taken in David G. Calderwood, Voices from the Dust: New Insights into Ancient America (Austin, Tex.: Historical Publications, 2005).

29Durán, Historia de las Indias de Nueva España, 1:11; translation mine.