Another Idea for Nephi’s Ship

Another Idea for Nephi’s Ship

Article and photos, except where noted, by Stephen L. Carr

(with a short article about an LDS man who built a similar craft

and comments from George Potter and Alan Miner)

In September 2000, I was fortunate to have taken a BYU trip along part of the trail that Lehi and his family took in 600 BC, particularly from Jerusalem to the fount of the Red Sea (Gulf of Aqaba), partway down the southeastern shore of this gulf; then again from Nahom, in the country of Yemen, to the east and ending at the most likely place for the land Bountiful on the Omani coast of the Indian Ocean. This trip was led by Warren Aston, LDS explorer from Australia and discoverer of Lehi’s land Bountiful and co-discoverer of the site of ancient Nahom; and Lynn Hilton of Utah, who lived and taught at a university in Saudi Arabia. The BYU coordinator was Greg Witt. (I repeated much of the same tour in October 2004 with a small group led by Warren Aston.) During the first trip, one day at our hotel after visiting the site of Wadi Sayq and Khor Kharfot, I gave a presentation on the following information. I’ve since been asked to provide this presentation in a BMAF article.

After leaving Jerusalem and traveling down the eastern shore of the Red Sea to Nahom, then eastward across the southern edge of the Rub’ al Khali (the notorious empty quarter desert of the Arabian Peninsula), and after a period of at least eight years, the traveling Lehite colony finally was led by the Liahona to descend Wadi Sayq, in the extreme south of what is now Oman, to finally come to a rest at the mouth of the wadi, a small inlet called Khor Kharfot. This inlet was then, and is now, completely uninhabited by humans, although there are traces of some temporary occupation approximately 500 years ago. After resting up for a short while, Nephi was called by the Lord, through the Holy Ghost, to climb the mountain, which is located on the ocean (Irreantum) right on the edge of the inlet. Of interest is that it is the only mountain in the neighborhood. When told to go up the mountain, there was no question as to where it was, as it is the only one. Upon ascending the mountain and praying, he was instructed to build a sailing vessel (Joseph Smith, in his translation of the plates, used the word ‘ship’). Nephi then did not ask how to build the ship, instead he asked the Lord to show him where to find ore from which to fashion tools with which to build the ship. The Lehite colony was alone at Khor Kharfot and had no one else to ask for help. Although, apparently, there was a ship-building town some 40-50 miles on the coast north of Khor Kharfot, the Lord desired that Lehi’s group be isolated so that he, the Lord, would have control over how the vessel was to be constructed. Nephi specifically tells us that he “did not work the timbers after the manner which was learned by men, neither did I build the ship after the manner of men; but I did build it after the manner which the Lord had shown unto me; wherefore, it was not after the manner of men (1 Nephi 18:2). This vessel then, may or may not have appeared like boats or ships of the age then or since. And, considering the isolated nature of the work, and the primitive tools that Nephi would have been able to manufacture by casting into molds carved in the ground, the boat or ship probably did not look like the well-known picture painted by Arnold Friberg, which has the appearance of a great Spanish galleon.

Nephi may never have seen a sea-going vessel in his youth growing up in land-locked Jerusalem, but must have seen some of the Arab dhows in Ezion-Geber when the group passed by on their way to the valley of Lemuel. So, he probably had a pretty good idea of what a ship looked like, but the Lord gave him different directions, of which we know essentially nothing.

This is Khor Kharfot, the inlet at the mouth of the canyon, Wadi Sayq, as seen from a half-mile out into the Indian Ocean.

Nephi’s 2500-foot-high mountain is to the left. The hill to the right is not as high and is more of a long plateau.

Consider the only tools that Nephi would have been able to fashion with his crude furnace or smelting facility. We now know that there are deposits of both copper and iron ore within a decent distance from Khor Kharfot to make them essentially readily accessible for making tools. Copper ore melts at a lower temperature than does iron ore, and for Nephi’s purposes, copper tools, although not as strong as iron tools, may have been completely adequate. The actual type of metal ore is never mentioned when referring to these tools and implements. The tools required would have been hatchets or axes for felling trees and cutting off branches, adzes for shaping the logs, bow drills for boring holes in the logs, cold chisels, sledge hammers with which to pound wooden pegs into the logs. There is also the possibility that iron bolts could have been cast with heads on one end to drive into the logs instead of pegs or dowels. The one tool that the builders could really have made good use of but probably didn’t have with them is a saw. A forged, steel saw is several degrees of technology higher than the cast metal tools they could make; and unless they brought one or more with them from Jerusalem, they were out of luck. Even if Nephi could have cast a blade with teeth carved in the mold, the item would have been too thick to have operated well and the teeth would not have been sharp enough to have helped. Without a saw or a plane to make straight, even cuts and edges, it is doubtful that Nephi could have made planking that would have been watertight, such as would be required for a hulled and keeled ship. Even the best of adzes would not be able to shape a boat’s timbers smoothly enough to make the vessel watertight.

.png)

Not knowing how the Lord instructed Nephi to build the vessel ‘not after the manner of men,’ allows one to conjecture on the type of boat or ship that could have been constructed. I have considered for many years the possibility that with a minimum of tools and people to labor, that a simple vessel that may have looked differently from most other boats that plied either the Mediterranean Sea or the Indian Ocean, could have been a substantial raft of sorts, with a prow and sides built up to withstand the waves, yet sturdy enough to have lasted for the extensive Pacific Ocean voyage. Even then, the party on board probably stopped several times as the craft wended its way through the Indonesian archipelago, acquiring foods as needed, and possibly making repairs as needed, before finally setting off completely from the last easternmost island.

Some have thought that it would be necessary to have a large, hulled ship with plenty of room for provisions, drinking water, and ballast in order to make the voyage. For a human cargo of between 30 to 50 people, most of them children, it may not have been necessary to have such a commodious craft. The Lord would have known how much food and water the floating colony would have required on the journey, and instructed Nephi on the amount of space that would have been needed for storage.

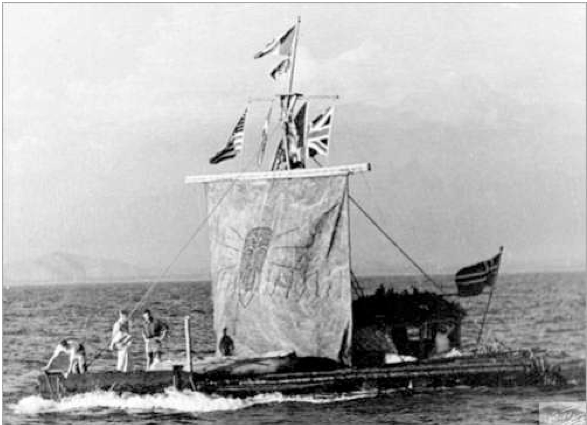

Consider the Kon-Tiki raft, built and sailed by Norwegian explorer and anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl in the late 1940’s. It was very small, carried 8 men with no way of resupplying food and water the 4300 nautical miles between Peru and the Polynesian islands, yet the little raft sailed along without problems of swamping or capsizing or running out of food and water. Besides the provisions they brought with them, the cook walked around the deck several times a day and gathered up the flying fish that landed on the deck, and cooked them for their meals. Plus, they often caught larger fish with hooks or bare hands. Heyerdahl mentions, “There were fish enough in the sea to feed a whole flotilla of rafts.” Occasional rain showers provided all the fresh drinking water the crew needed.1

A three-quarter view of the Kon-Tiki raft with several of the crew on the prow, a simple sail, and cabin-like shelter on the aft section for when the weather got extremely foul or to shade them from the tropical sun. Their average speed was 42.5 nautical miles per day, and on one day even sailing 71 miles. Photo by Thor Heyerdahl’s crew in the book, Kon-Tiki.

View of Kon-Tiki from the rear, again demonstrating the rudimentary cabin, simple sail, and long steering rudder. This raft had a bare minimum of bulkheads to keep water from flowing onto the deck. In fact, Heyerdahl states, “Many thousands of tons of water poured in astern daily and vanished between the logs.” There was obviously no concern about bailing out a hold-full of water that would be necessary with an enclosed, hulled, and keeled ship. Photo by Thor Heyerdahl’s crew in the book, Kon-Tiki.

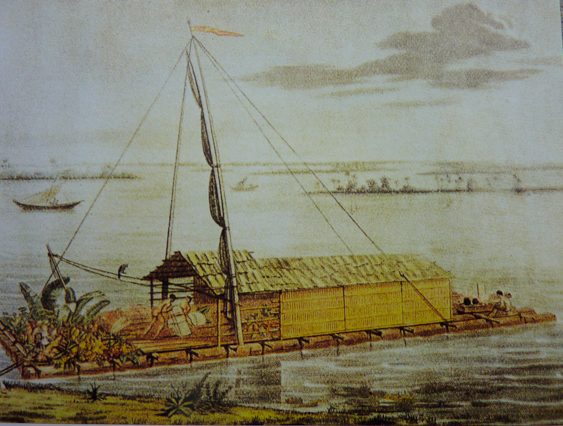

One interesting consideration would be, how much food would be needed on an expedition of the type that the Lehites took. Even with all the fish that would be available, it would probably be advisable to have some alternatives or supplements. Nephi specifically mentions taking “. . . . fruits and meat from the wilderness, and honey in abundance, and provisions according to that which the Lord had commanded us, ….” (1 Nephi 18:6). One interesting prospect that I had never thought of until seeing a picture in the JBMS, was of literally planting a vegetable garden on the rear deck of the raft. Ecuadorian raft travelers did exactly that when required to transport themselves for long distances. The folks from Ecuador would have sailed with plenty of fuel for their cooking, but the Lehite voyage probably did not take bulky fuel and so undoubtedly had to eat the fish raw or salted in brine pots. If they didn’t have a garden on board, their fruits, vegetables, and meats would likely have been dried.2

This 1810 drawing by Alexander von Humboldt depicts a raft from Ecuador with a garden at one end and cooking facilities at the other. Nearly identical rafts were used in southern China and Vietnam for thousands of year and were likewise steerable and safe. Sorenson, JBMS, p. 13.

The lower sections of Wadi Sayq down into Khor Kharfot itself are studded with tall, straight trees of the fig genus. They are substantial hardwood trees, the logs of which would have been able to hold up during the ocean trip. Warren Aston has also noted that, at least at the present, those tall trees grow only in the Kharfot area of Dhofar in southern Oman. He also agrees that, “Building a large, ocean-going raft would still have been a significant project, but one more closely matched to the materials and labor resources at hand.”3

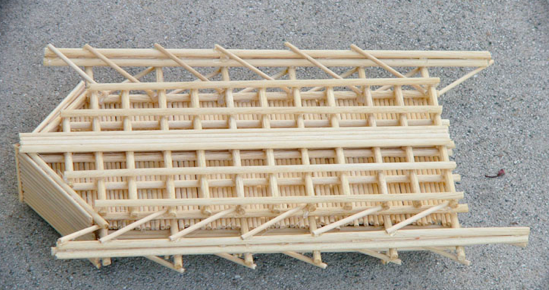

The reason for a raft design is that it could be constructed with relatively few, very basic tools as previously mentioned in a reasonable amount of time. (Some Book of Mormon authorities think that the group may have resided in Bountiful for two to four years while building the ship and gathering farm seeds in plentiful supply, as well as foodstuffs that they would take with them.) Heavy axes would have been required to drop the trees, then smaller hatchets used to remove limbs, followed by adzes to shape some of the logs that were awry and to knock off the ubiquitous knots.

Now, to the drawing and constructing of a model of a proposed raft. I don’t know how familiar Nephi may have been with rafts as a youngster growing up, etc., but I don’t think that a large, ocean-going raft would have crossed his mind until reaching the Irreantum. I began thinking of this concept in 1989.

.png)

Pictures of Arab dhows that I have seen, even fairly good-sized ones, show them to have quite a deep draft but not much deck space. A raft of this present design allows plenty of living space for each married couple and their children. I realize that the custom then, at least among Arab Bedouin, was that the man slept alone, with the wife and younger children in a separate tent. I don’t know whether the Jews had similar ways, but, of necessity, there would have had to have been some compromising and combining of compartments. Each of the apartments would have been approximately 10-feet square, with a storage room of the same size and a latrine of similar size as well. This latrine could have been open to some extent to the sea for sanitary and cleaning purposes.

Another reason for the common deck of some 10 feet wide by up to 50+ feet long was to allow the little children, of which there were many, to run and play during the daytime. It would also have been the place where Laman, Lemuel, and the sons of Ishmael and their wives would have had space to make merry inappropriately (1 Nephi18:9). Then, there would have been a mast where Nephi could have been tied up to (1 Nephi 18:11).

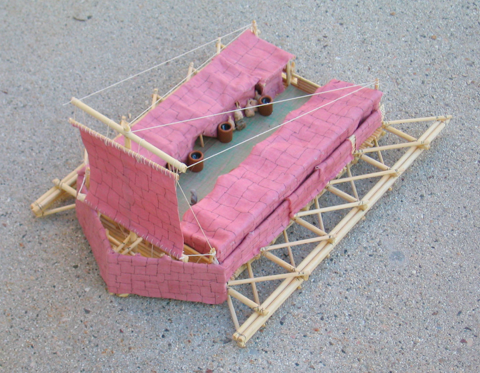

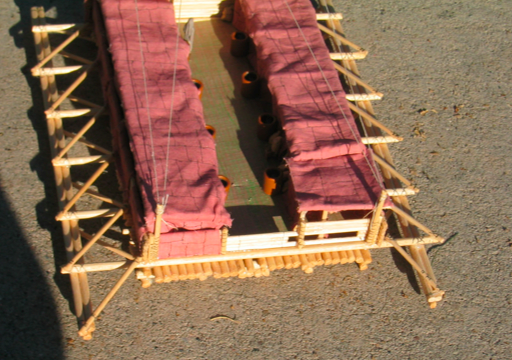

Above: Basic construction of upper, living quarters part of the raft. Two sets of timber bulwarks in the front to ward off waves while moving forward. Side and end bulwarks to keep side waves from entering the boat. Latrine to be built in the right rear corner

I envisioned the raft to be quite heavy and solid on the bottom, with several layers of logs in the center to form a sort of keel. This would have allowed the raft to ride low in the water for stability, with the outrigger pontoons attached to contribute even more steadiness. Perhaps this is the prototype for the Polynesian outrigger crafts for which they are noted – if Hagoth had continued the tradition of this boat, several hundred years later, and one of them got blown off course and wound up in the islands (Alma 63:8). The log work along the front and sides could have been built of somewhat lighter logs than the base, to provide a breakwater and to keep anyone from sliding off the sides during a storm.

Underneath side of raft showing heavy timber construction that would be under the water surface, along with outrigger pontoons to provide stability. Most timbers are longitudinal in order to keep craft pointing forward as much as possible.

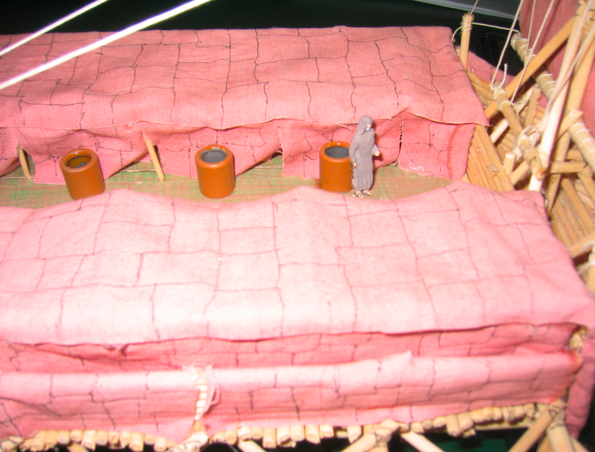

I envision the builders erecting some posts and headboards, and then the folks could have taken down their tents and spread them across the framework to provide housing for each family, made partitions between the cabin-tents to separate each family, plus a storeroom for food and supplies.

These could have been augmented by animal skins. (I wonder what the group did with their camels when they got ready to sail. They would not have eaten them because the camel was prohibited by the Mosaic Law (Lev. 11:4), but they could have killed them to use their hides as part of their tent-cabin structures.) On my model, I built the tents so that they sloped downward and to the sides of each compartment in order to collect rainwater. If the large cisterns that I made for the raft would have been unlikely, due to the size of the furnace that would have been required to bake them, then smaller cisterns and jugs could have been made; or larger woven baskets lined on the inside with pitch and sap could have been made, instead.

Left side of raft showing storage compartment on the right side and covered latrine. Latrine has privacy entrance. There is plenty of room on the deck between living accommodations to allow for Laman and Lemuel and the sons of Ishmael and their wives to dance, make merry, and be rude. The sail, made from hide panels, could be raised and lowered as needed. If I were to change anything it would be to employ the A-frame masts that Heyerdahl used in his Kon-Tiki. (See his second photo.) The sail would have been much more stable than using a single vertical mast.

While the men and older boys were in the process of making tools and building the vessel, the women, girls, and younger children could have been weaving floor mats, mattresses, and various baskets and containers from the profusion of reeds growing around the lagoon at the mouth of the wadi. I can see a floor covering of 4-5 layers of these mats, which would provide a softer floor than the hard logs, and would have allowed rainwater to filter through, yet keep the ocean waters from splashing up between the logs.

Completed raft with leather hides or woven camelhair panels along bow and sides to further retard water entrance. Tent roofs are sloped between each family’s living quarters to allow rainwater to course down into storage casks. Father Lehi stands by his compartment.

Another thing should be considered – although a couple of writers agree that Nephi went to the mountain to receive revelations, they go on to state that even then he couldn’t possibly have built the ship without the constant tutelage of a master shipbuilder. I prefer to take Nephi and the Lord at their word and have Nephi learn all he needed to know from the Lord’s instructions, as the master shipbuilder, as to the methods of the boat’s construction (1 Nep. 18:3). Also, there is no hint that Nephi had to take his ship out for a test run, teaching his family their duties with the ship-rigging, etc. Again, Jehovah, through the Holy Ghost, taught Nephi how to launch the boat into the sea and then sail it the first time, with the guidance of the Liahona, without the need for a preliminary shakedown cruise.

The rear end showing the latrine in the corner. At the time I took these photos, I had not yet installed the rudder. Woven reed mats could have been laid down several layers thick to keep the deck as free from water as possible. Rainwater would be able to seep through but ocean water would not be able to splash up between the logs and through the layers of matting.

The following commentary is from John L. Sorenson’s article in JBMS, as cited in the references. The quotations he uses are in his original article, thus the difference in numbering sequence.

“A question naturally arises as to whether vessels and nautical skills were available to account for the early voyages. Contrary to the picture we were once taught about ‘primitive’ sailors timidly avoiding the open sea until an intrepid Columbus made a breakthrough, evidence now clearly establishes that sailors long ago ventured widely. As long ago as 50,000 years bp (before the present), Australia's first settlers reached that continent across as much as 95 miles (150 km) of open sea, and the Solomon Islands were populated from 105 miles (170 km) away by 29,000 years ago.62 Balsa-log rafts (functionally they were steerable ‘ships,’ not what we think of under the term rafts) like the Kon-Tiki vessel of Thor Heyerdahl were preceded by early Ecuadoran craft that sailed up and down the Pacific coast of South and Middle America apparently from 2000 BC on.63 However, they, in turn, were modeled on rafts of unknown age from China and Southeast Asia.64Three modern replicas of pre-Columbian rafts constructed in Ecuador in the traditional form were sailed in 1974 as a fleet over 9,000 miles to Australia.65 Many other craft, some of them remarkably small and ‘primitive,’66 have been sailed in modern times across various ocean routes; one veteran small-craft sailor reports that ‘it takes a damned fool to sink a boat on the high seas.’”67

Finally, one last comment from Warren Aston, “It seems safe to conclude that raft design not only meets all the scriptural requirements for Nephi’s ‘ship’ but remains the minimal and most feasible structure that could be constructed under the circumstances. We should therefore consider it the leading candidate for the ship that carried Lehi’s group to the New World."3

The accompanying article by Warren Aston, published in Meridian Magazine, January 31, 2011, discusses the raft concepts of DeVere Baker, an LDS explorer of note in the 1950’s. I was unaware of his exploits and writings when developing my own ideas for Nephi’s raft because, when his material was published in 1958-59, I was in the mission field and had no exposure to his feat and story.

by Warren Aston

(this article first appeared in Meridian Magazine on December 4, 2011,

and is printed here witih permission of the author and Meridian Magazine)

Brigham Young would have loved DeVere Baker. From the tabernacle pulpit President Young had once urged church members onto bigger and better things now they had found their place in the mountains. “There is too much of a sameness among this people,” he complained. “Away with stereotyped Latter-day Saints!” Although he was not born until 1915, DeVere Baker was one early member of the church who seemed determined to live as anything but a stereotyped Mormon.

Born to devout Mormon parents, DeVere had a fairly conventional upbringing in the small Utah town of Tremonton, north of Salt Lake City. However, while his childhood world lay hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean, he developed a fascination with the sea and with anything to do with ships. Unlike other boys his age, DeVere dreamed of sailing oceans much larger than the Great Salt Lake that lay just a few miles west of the family farm.

DeVere got his chance when World War ll arrived and he moved to California. Here his dreams took shape. To finance them and also feed his growing family, he developed a very successful shipyard that did work for the Navy. DeVere was serving as bishop of the Petaluma Ward when he suddenly became convinced that the plausibility and truthfulness of the Book of Mormon could be demonstrated by showing the world that a long ocean voyage was quite possible using the sea currents and a simple raft.

With the support of his wife Nola, DeVere sold virtually all their material possessions, including the family home, and set to work building what would be the first of five rafts named in honor of the prophet Lehi. This began an effort that would consume most of his life.

A lesser man may have omitted the failures and more embarrassing details when writing about his great quest, but in his 1959 book “The Raft Lehi IV: Sixty-nine Days Adrift on the Pacific Ocean,” Baker seemed determined to record almost everything for posterity. This included crew defections and falling over at a beach press conference after putting both his legs into one leg of his bathing costume. Launched amidst much fanfare in July 1954, the first Lehi wallowed off San Francisco harbor for six days before an SOS went out. Battered by bad weather and heavy seas the crew were eventually rescued by a banana freighter. The abandoned raft was reported drifting south over succeeding years.

This initial failure only spurred DeVere on; a year later Lehi 2 was ready to sail. This time, however, the departure became a fiasco when a young crew member launched the raft prematurely before anyone else, including Baker, had boarded. DeVere quickly commandeered another boat to give chase and once he regained control of the raft had to continue the journey. Another severe storm rolled in. After just three days the crew had to be rescued by the Coast Guard and the raft drifted southwards to a landfall in a Mexican lagoon.

DeVere’s failure to get more than a few miles offshore began to draw scorn from the press. The California newspapers loved a good story, but now they and the much more orthodox Mormon press in Utah turned their backs on these embarrassing developments, no longer reporting his efforts. The coastguard was tired of rescuing him.

Undaunted, DeVere locked himself away in a garage, emerging months later with Lehi 3. Lacking funds to complete the raft, what rolled out of the garage was simply a fragile plywood cabin without the actual raft beneath. This time, however, Baker successfully floated the strange craft, with his dog Tangaroa and one crewmember aboard, down the coast of California, eventually reaching Los Angeles. The feat brought renewed publicity and interest in his quest. A sponsor emerged, enabling DeVere to build the raft beneath the cabin, which then became the 24-foot long Lehi 4.

The Lehi 4 set sail July 5th, 1958 from Redondo Beach with four crew plus Tangaroa. Despite storms, heavy winds and shark encounters the raft stayed on track, easily demonstrating, as others have done, that one can live at sea off rainwater and fish for long periods. After a total of 69 days of sailing some 2100 miles across the northern Pacific, Baker and his small crew made landfall in Maui in the Hawaiian islands.

Thousands of locals applauded their safe arrival and the publicity was enormous. DeVere’s wife and their two daughters were flown out to Hawaii to join him. The successful voyage brought back favorable press coverage, lectures, TV interviews and an appearance on ‘This is Your Life.’ The BBC featured the tall and charismatic DeVere in a series about explorers under the by-line “Danger is my business.” His persistence and the success of the fourth voyage restored a measure of respectability to DeVere Baker. He felt vindicated and announced plans for more ambitious sailings and a film.

For a time it seemed that Baker would go on to achieve greater successes on the high seas. But, as time passed and the highly publicized feats of Thor Hyerdahl’s rafts overshadowed Devere’s success, sponsors failed to emerge. A public now more interested in post-war economic catch-up than the Book of Mormon’s truthfulness ensured that these expanded dreams remained elusive.

Nor were Baker’s dreams confined to the ocean. In a unique combination of science-fiction and Mormon theology, he authored several stories focused on a beautiful alien girl named ‘Quetara.’ A human scientist is kidnapped by her crew and falls in love with her, learning in the process how God came to be, billions of years previously, and how evolution allowed the endless variation of species to develop on each world in a grand, perpetual Cosmic experiment overseen and controlled by Deity. A subtext of this was ostensibly good latter-day doctrine - that countless other worlds, including, of course, the wise and alluring Quetara’s own planet, were inhabited by people just like us.

This was heady stuff for the nineteen forties, but it gave DeVere Baker a vehicle to present elements of his religion and to introduce the ultimate reason for all of his raft efforts. For, in fact, Baker’s plans foresaw much more than a sailing from his adopted California across the Pacific. Ultimately, he planned to literally recreate Lehi’s journey and sail from Arabia to America.

The stages of the journey, including the final twenty-plus-thousand mile crossing of the Pacific Ocean, were all carefully planned. Such a feat would force an unbelieving world to accept the Book of Mormon as God’s Word no less than the Bible. Baker hoped this would turn the tide of godless communism, which he saw as humanity’s greatest threat.

Twenty years ago, in December 1990, after a long period of poor health, DeVere Baker passed away in Provo, Utah. Despite sacrificing his money, health and most of his best years to a dream most Latter-day Saints would have total sympathy for, he died largely unknown and forgotten. Although he had earned his place in maritime history, his adventures were both out of print and out of favor. His dream of recreating Lehi’s ocean voyage remains unfinished, perhaps awaiting another adventurous spirit to rise to the challenge.

The Lehite voyage from Old to New World is, after all, by far the least understood aspect of the incredible saga that opens the Book of Mormon. Another decade and a half would pass before LDS researchers would begin to appreciate the pioneering contributions of DeVere Baker, someone who was anything but a stereotyped Mormon.

Warren P Aston

References:

1. Thor Heyerdahl, Kon-Tiki, Across the Pacific by Raft, Rand McNally & Co., Chicago, 1950.

2. John L. Sorenson, “Ancient Voyages Across the Ocean to America,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies, Vol. 14, Number 1, Neal A. Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, 5-17.

3. Warren Aston, personal communication.

62. Clive Gamble, Timewalkers: The Prehistory of Global Colonization (Phoenix Mill, England: Alan Sutton; Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 214—30.

63. P. Norton,"El señorio de Salangone y la liga de mercaderes: el cartel spondylus-balsa," in Arqueologia y etnohistoria del sur de Colombia y norte del Ecuador, comp. J. Alcina Franch and S. Moreno Yánez (Miscelanea Antropológica Ecuatoriana, Monográfico 6, y Boletin de los Museos del Banco Central del Ecuador 6) (Cayambe, Ecuador: Ediciones Abya-Yala, 1987); Joseph Needham and Lu Gwei-Djen, Trans-Pacific Echoes and Resonances: Listening Once Again (Singapore and Philadelphia: World Scientific, 1985), 48—49.

64. Clinton R. Edwards, Aboriginal Watercraft on the Pacific Coast of South America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965); "New World perspectives on pre-European voyaging in the Pacific," in Early Chinese Art and Its Possible Influence in the Pacific Basin: A Symposium Arranged by the Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, New York City, August 21—25, 1967, ed. Noel Barnard in collaboration with Douglas Fraser, vol. 3, Oceania and the Americas (New York: Intercultural Arts Press, 1969), 843—87.

65. Vital Alsar, La Balsa; The Longest Raft Voyage in History (New York: Reader's Digest Press/E. P. Dutton, 1973); Pacific Challenge (La Jolla, CA: Concord Films [dba ALTI Publishers]), 1974, an 84-minute video.

66. Charles A. Borden, Sea Quest: Global Blue-Water Adventuring in Small Craft (Philadelphia: Macrae Smith, 1967); Alan J. Villiers, Wild Ocean: The Story of the North Atlantic and the Men Who Sailed It (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1957).

67. Hannes Lindemann, Alone at Sea, ed. J. Stuart (New York: Random House, 1957).

Both George Potter and Alan Miner responded:

From Step by Step Through the Book of Mormon (Unpublished) by Alan C.

Miner. Excerpt taken from Discovering The Lehi-Nephi Trail, Unpublished

Manuscript (July 2000), pp. 211, 235-242 by George Potter & Richard

Wellington,

1 Nephi 18:8 We Had All Gone down into the Ship . . . We Did Put Forth into the Sea:

According to Potter and Wellington, the fact that Nephi mentions that they had "gone down into the ship" (1 Nephi 18:8) implies that Nephi's ship was tied to a mooring before they disembarked. Moored next to a port seawall, Nephi would have used a gangplank to "walk down" into the ship. This appears to be the picture Nephi described as they put their supplies aboard the ship, and as the family entered the ship for the final voyage. Nephi also says that they "put forth into the sea" (1 Nephi 18:8), once again implying that the ship was initially in a port that was somewhat protected from the sea and had to "put forth into the sea." Nephi's words also bring up the necessity of a port for building and launching a ship. With this in mind Potter and Wellington made an analysis of all the possible ports in Dhofarusing criteria gleaned from the text and also from historical and cultural settings. The following criteria were listed for Nephi's port:

1. The port would have to be large enough to accommodate a large ship.

2. The port would have been protected year round from monsoon winds.

3. The port should show evidence of ancient use.

4. It would have been open to the sea during the time of Lehi.

5. It would have had protection from high surf. 6. It was only necessary that Nephi had a place to moor his ship while finishing it.

7. Nephi wrote that the place had "much fruit" (1 Nephi 17:5) 8. There were apparently cliffs above deep water nearby because of Laman & Lemuel's attempt to throw Nephi to his death. (1Nephi 17:48)

9. Trade with India would have been necessary for large timbers suitable for shipbuilding. 10. There would need to be large domestic timbers nearby.

11. There would need to be access to thousands of coconuts or other material for ropes. 12. Sails would need to be available or the material to make canvas for sails.

13. Iron ore to make tools was nearby. (1 Nephi 17:10)

14. Experienced shipwrights were needed.

15. Experienced ship captains were needed in order to teach Nephi to captain a ship. 16. There was apparently a mountain nearby where the Lord instructed Nephi. (1 Nephi 17:7; 18:3)

17. Sailors capable of teaching Nephi's crew needed to be

available along with facilities for conducting sea trials. 18. "Stones" to make fire with, or flint was needed nearby. (1 Nephi 17:11)

From the results of this comparison Potter and Wellington found only five serious candidates for the place where Nephi built and launched the ship: Reysut, Khor Suli, Khor Taqah, Khor Rori, and Mirbat--all on the Salalah plain. Interestingly, they found no evidence that Khor Kharfot was ever a port in Nephi's time or at any other time for that matter. By far the strongest candidate was the port of Moscha at Khor Rori, especially when one considers the village of Taqa and Khor Rori as one site, as they are only two miles apart

Steve Carr wrote the following review of the above response:

In 1990, Warren Aston, an LDS scholar and researcher from Australia, developed a list of 14 criteria from what the Book of Mormon had to say about the land Bountiful on the Arabian Peninsula. In 1992, he set out to discover where this might be along the coast of Yemen and Oman. Because he was Australian he was allowed to do this, as Americans were still suspect during this time. He located 8 inlets that could be construed to be essentially eastward from Nahom, which he had also discovered in the interior of Yemen earlier. Of those 8, only 2 met more than half the criteria, and the two each met 13 of the criteria - Wadi Sayq/Khor Kharfot and Khor Rori at Salalah. The one criterion that was missing from both was the location of metallic ore from which to make tools. Since then, ore bodies of both copper and iron have been found. These ore bodies are roughly equidistant from both Wadi Sayq on the south and Salalah on the north. So, the ore deposits would have been the same for whichever location was the land Bountiful. Below are the 14 criteria that Warren established.

Requirements for the Land of Bountiful on the shore of the Arabian Peninsula

1- Same approximate latitude as Nahom (nearly eastward from Nahom) - 1 Nep. 17:1.

2- Easily accessible from the high interior plateau - 1 Nep. 17:1.

3- Abundance of fruit - 1 Nep. 17:5; 18:6.

4- Wild honey available - 1 Nep. 17:5: 18:6.

5- Shoreline fronting a large expanse of water - 1 Nep. 17:5-6.

6- Permanent supply of fresh water. (Not mentioned in the scripture, but obviously necessary for a prolonged stay.)

7- Mountain nearby where Nephi could go often to pray - 1 Nep. 17:7: 18:3.

8- Ore in the vicinity for making tools - 1 Nep. 17:9-10, 16.

9- Flint-type stones for producing fire - 1 Nep. 17:11.

10- Cliff nearby from which the brothers could have thrown Nephi into the sea - 1 Nep. 17:48.

11- Large trees nearby big enough to use for ship timbers - 1 Nep. 17:8; 18:1.

12- Living area on a higher level than the beach where the ship was being built - 1 Nep. 18:5.

13- Suitable winds and ocean currents to take the ship out into the ocean - 1 Nep. 18:8.

14- No nearby population from which to obtain tools, hiring help in building the ship, buying supplies, etc. (Not mentioned, but suggestive.)

In reply to the questions that have come about as the result of Potter and Wellington's book - from what I understand, neither Potter nor Wellington had visited Wadi Sayq/Khor Kharfot at the time the book was published. I have visited both Khor Kharfot and the Salalah area with Khor Rori twice, in 2000 and 2004. And, although I'm not an expert on the country, I have studied the locations carefully and in person. My comments below will be in red.

1 Nephi 18:8 We Had All Gone down into the Ship . . . We Did Put Forth into the Sea:

According to Potter and Wellington, the fact that Nephi mentions that they had "gone down into the ship" (1 Nephi 18:8) implies that Nephi's ship was tied to a mooriing before they disembarked.

Moored next to a port seawall, Nephi would have used a gangplank to "walk down" into the ship. This appears to be the picture Nephi described as they put their supplies aboard the ship, and as the family entered the ship for the final voyage. Nephi also says that they "put forth into the sea" (1 Nephi 18:8), once again implying that the ship was initially in a port that was somewhat protected from the sea and had to "put forth into the sea." Nephi's words also bring up the necessity of a port for building and launching a ship. With this in mind Potter and Wellington made an analysis of all the possible ports in Dhofar using criteria gleaned from the text and also from historical and cultural settings. The following criteria were listed for Nephi's port:

Regarding going down into the ship: At Khor Kharfot, there is a narrow plateau at the base of the only mountain present, right on the seacoast and forming one side of Wadi Sayq and Khor Kharfot. There is archaeological evidence that people lived on that plateau in the distant past. (The reason they would not have stayed down on the beach or lower areas is that those areas are either marshy or are full of yellow sand crabs.) The end of the plateau, incidentally, juts out into the sea, about 80 feet above the rocks and water, and would have been the place from which Laman and Lemuel were threatening to toss off Nephi. So, when it came time to load the ship, the party would have gone "down" to the ship from where they were quartered.

1. The port would been large enough to accommodate a large ship. According to my suggestion of a possible raft of sorts (and even if a boat with a shallower draft than a deep-hulled ship) the port would not have been particularly large in which to build the craft. The inlet at Khor Kharfot is plenty large enough for that purpose.

2. The port would have been protected year round from monsoon winds. This applies to Khor Kharfot, also.

3. The port should show evidence of ancient use. As mentioned, the habitation area shows archaeological evidence, as does the area all around the inlet.

4. It would have been open to the sea during the time of Lehi. The inlet at Khor Kharfot is at present closed off by a sandbar, as is the port at Khor Rori. Hydrogeologist estimate it has been that way from probably 500 years, due to various wind and wave currents, but was probably open 600 BC.

5. It would have had protection from high surf. The inlet runs far enough up into Wadi Sayq that it would have been protected.

6. It was only necessary that Nephi had a place to moor his ship while finishing it. Same as #5.

7. Nephi wrote that the place had "much fruit" (1 Nephi 17:5) Wadi Sayq is full of fruit - wild dates and figs, specifically, and apparently grapes in times past. Plus, the nearby, easily accessible cliffs contain caves, even now, with bees making honey.

8. There were apparently cliff above deep water nearby because of Laman & Lemuel's attempt to throw Nephi to his death. (1 Nephi 17:48) See the comments at the beginning.

9. Trade with India would have been necessary for large timbers suitable for shipbuilding. There is no suggestion at all in the Book of Mormon that such would be necessary or even advisable. It is doubtful that the Lehite colony would have had the money with which to purchase expensive lumber transported all the way from India, or anywhere else.

10. There would need to be large domestic timbers nearby. Wadi Sayq has many large trees, even now, 2700 years after the Lehite colony left there, with which to build a ship/boat/raft. Further, these trees are available right at the inlet of Khor Kharfot, whereas at Khor Rori, the nearest large trees are between 5 and 8 miles inland and, at present, there are no large trees, only smaller, wind-swept ones. It is unknown what the trees may have been like in Lehi's time.

11. There would need to be access to thousands of coconuts or other material for ropes. Again, at present, and presumably for centuries and millennia earlier, Khor Kharfot is full of coconut palms.

12. Sails would need to be available or the material to make canvas for sails. Sails could have been made from many materials. The Lehites could have made sails from their tents. Palm fronds could have been woven and tied together, if necessary.

13. Iron ore to make tools was nearby. (1 Nephi 17:10) See the first paragraph.

14. Experienced shipwrights were needed. There is no mention or even hint in the scripture of a shipwright being required or even consulted. Because the colony was isolated away from all other habitations and human contact, the Lord, Jehovah, was the shipwright. That is why He had Nephi come up to the mountain often to teach him how to construct the craft. No other tutor was needed.

15. Experienced ship captains were needed in order to teach Nephi to captain a ship. If the Lord could teach Nephi how to build the ship, He could also teach him how to steer and handle the vessel. Again, there is nothing said about any sort of tutor for Nephi. It's interesting that Potter and Wellington state that Nephi did go to the Lord, yet they have him relying more on a supposed master shipwright and captain to actually be in charge of the construction and operation of the craft. It seems that they almost completely leave the Lord out of the action. I prefer to think that Jehovah taught Nephi all he needed to know about the ship. If anything, he didn’t even need to consult a ship-builder, let alone rely on one.

16. There was apparently a mountain nearby where the Lord instructed Nephi. (1 Nephi 17:7; 18:3) There is a 2500-foot high mountain right on the coast at Khor Kharfot where Nephi went to receive his instruction. It is the only mountain within 20 miles. There would have been no question where when the Lord said, "Arise, and get thee into the mountain." At Salalah, there is a range of the Dhofar Mountains that run essentially north and south about 8 miles inland from Khor Rori. All the mountains are of the same height with saddles or passes between each pair of peaks. Nephi would not have known which of the half-dozen closest mountains were being referred to.

17. Sailors capable of teaching Nephi's crew needed to be available along with facilities for conducting sea trials. See #15. Again, no suggestion that any extra training would have been needed aside from what the Lord was teaching Nephi. There was also no hint as to the need for a trial at sea. When the boat was completed, the families took their possessions and foodstuffs and entered the vessel and pushed off at high tide into the surf.

18. "Stones" to make fire with, or flint was needed nearby.(1 Nephi 17:11) Flint rocks are found in abundance at the head of Wadi Sayq.

From the results of this comparison Potter and Wellington found only five serious candidates for the place where Nephi built and launched the ship: Reysut, Khor Suli, Khor Taqah, Khor Rori, and Mirbat--all on the Salalah plain. Interestingly, they found no evidence that Khor Kharfot was ever a port in Nephi's time or at any other time for that matter. By far the strongest candidate was the port of Moscha at Khor Rori, especially when one considers the village of Taqa and Khor Rori as one site, as they are only two miles apart.

Khor Kharfot probably never was a port like Khor Rori. The inlet is too small to have been considered as a location for a large, permanent city. But, for the type of vessel that the Lord had in mind, one that was unlike the crafts that were built "after the manner of men," it was eminently suitable. Potter and Wellington state that it was necessary for the Lehite colony to come to a location where there were shipwrights and sailing people. If that were the case, Nephi would not have had to go to the Lord to find where ore was in order to build the ship. He could have simply gone down to the local Home Depot and purchased all the professional tools and supplies he would have needed. Then, when Laman and Lemuel were in no mood to help with the enterprise, Nephi could have gone to the local labor board and hired as many willing workers as he would have needed. But, no, the boat was constructed entirely by Nephi and his brothers with the Lord as the Master Shipwright.

Potter and Wellington also state that there would have had to be tons of food put on board for the maritime journey. It would not have been necessary to load the ship with many tons of foodstuffs for the trip. Thor Heyerdahl made his 'Kon-Tiki' trip with very few provisions, as I mentioned in the original article. Further, it would not have been necessary to have had the trip take a year or more, and they could have stopped at various places to replenish food and supplies while going through the straits between Indonesia and Indochina.

Stephen L. Carr, 2012